人質司法に終止符を!訴訟 “End Hostage Justice!” Lawsuit

事実を争う被告人を勾留し続ける「人質司法」。

人質司法による長期間の身体拘束は、被疑者とされた人々の心身を蝕み、社会生活を破綻させ、仕事や家庭を崩壊させます。身体の拘束は究極の人権制約であるにもかかわらず、身体の自由が、否認や黙秘をしているだけで極めて容易に奪われています。

この訴訟は勾留や保釈の根拠となる刑事訴訟法の規定が憲法に違反することを訴え、人質司法に終止符を打つ訴訟です。

Under Japan’s “hostage justice” system, authorities impose prolonged detention—one of the most extreme forms of rights deprivation—on individuals simply for asserting their innocence or remaining silent. This inflicts severe physical and psychological harm, destroying lives, careers, and families. The system persists due to provisions in Japan’s Code of Criminal Procedure, which justify indefinite detention on vague grounds, such as potential evidence tampering.

This lawsuit, by four plaintiffs, challenges the constitutionality of these provisions, seeking to end the hostage justice system.

はじめに

皆さんは、もし自分が逮捕・勾留され、身体拘束を受けることになったとき、どのような生活を送ることになるか、知っていますか。

外に出ることはできません。外界から遮断された狭い部屋で、一日を過ごさなければいけません。施設内を移動するときですら、手錠・腰縄を付けての移動を強いられます。当然、学校に行くことも、会社に行くこともできません。

部屋の中で自由に過ごすこともできません。気楽に寝転がることもできません。携帯やパソコンを持つこともできません。食事の時間や内容、お風呂の頻度も決められています。トイレのドアもありません。普段の薬も飲めません。虫歯の治療すら困難です。

自由に人と会うこともできません。面会の回数や時間はわずかになります。狭い面会室の中で、すぐ横にはメモを取る警察官がいます。自分から誰かに会いに行くことはできず、誰かが会いに来てくれるのを待つことしかできません。

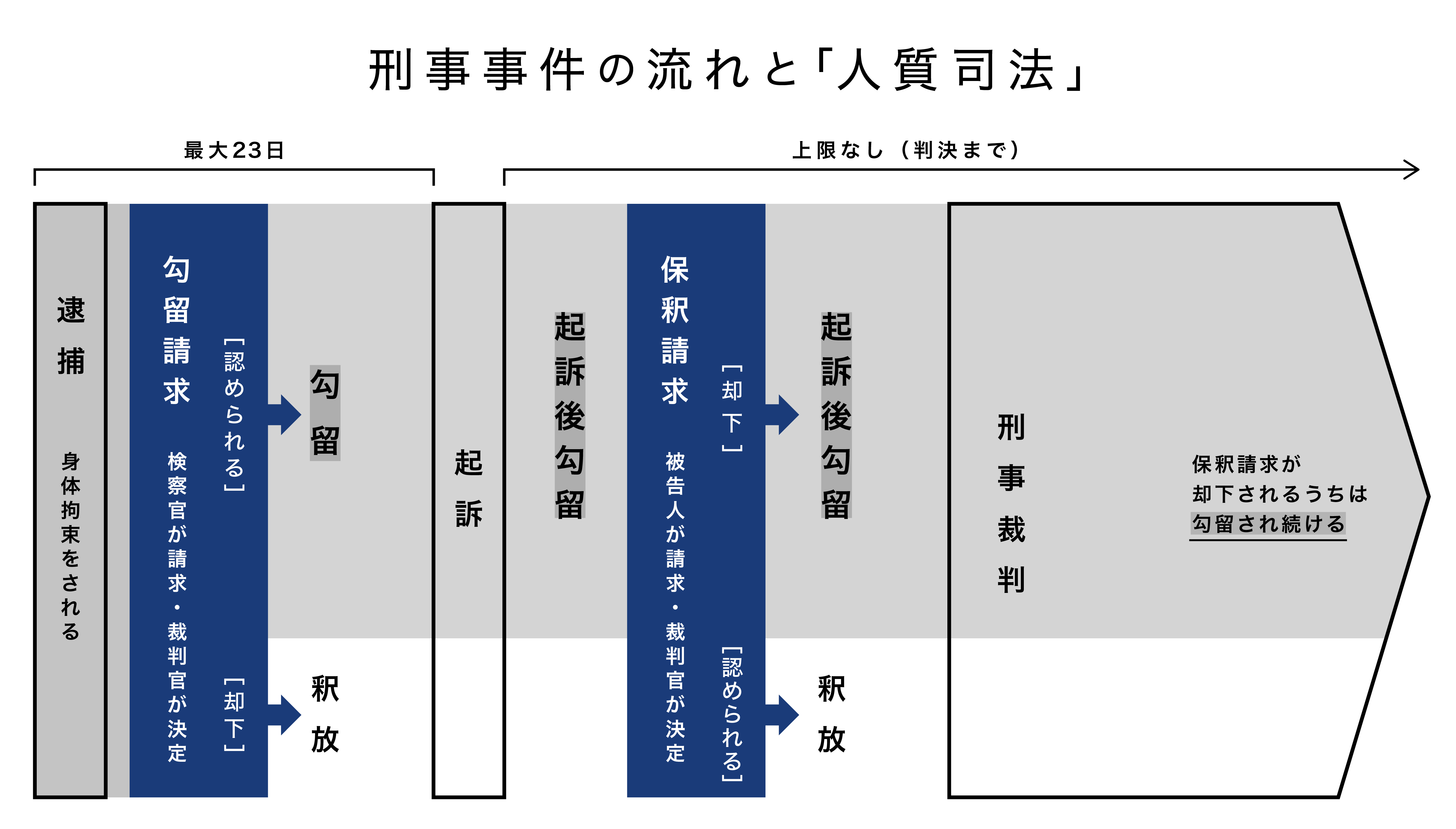

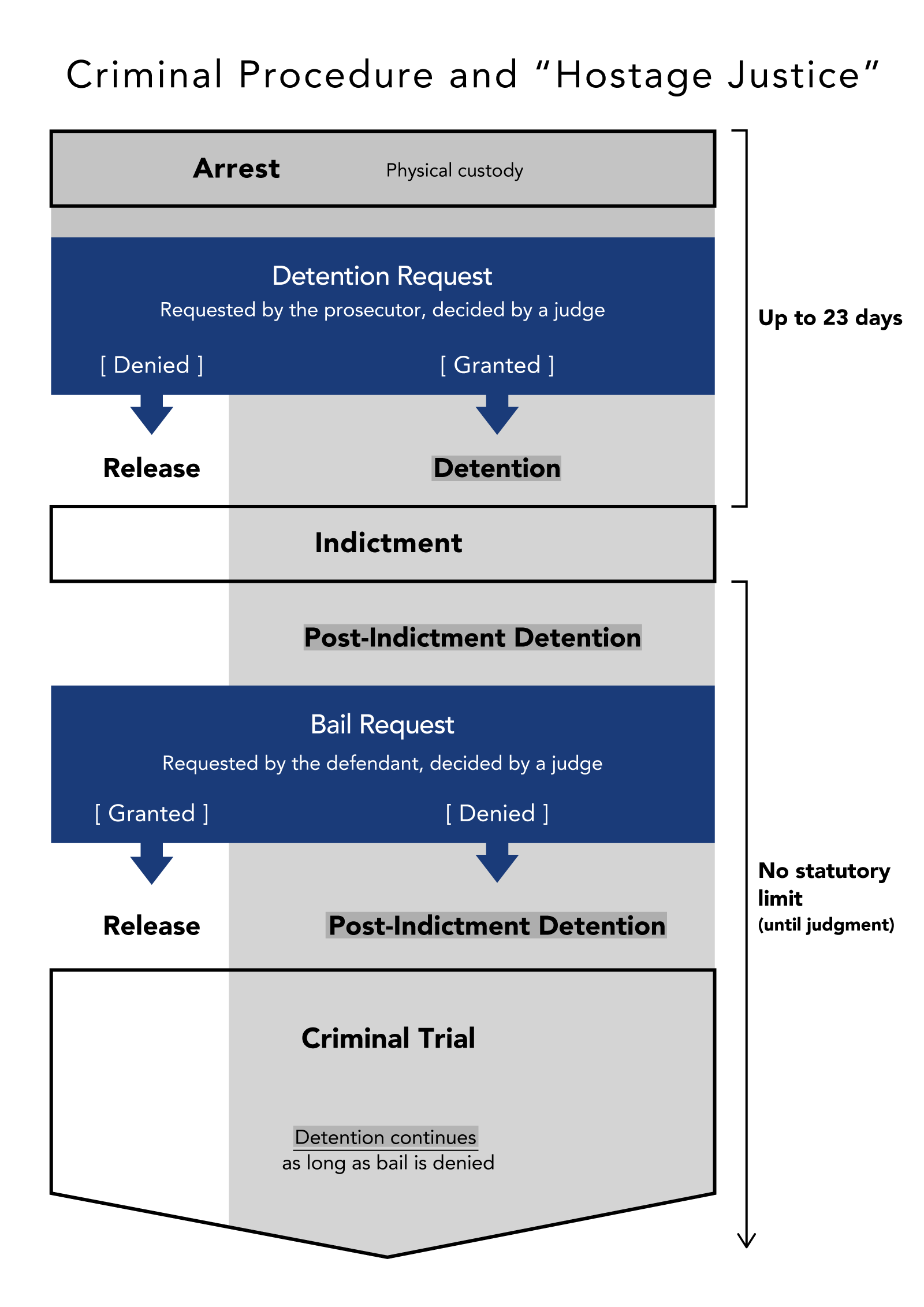

この生活が、起訴前には最大23日、起訴後には裁判が終わるまで無期限に続きます。いつ終わるかは分かりません。身体拘束からの解放を求め、保釈を請求しても、約3割しか認められていません。

終わりの見えない身体拘束がどれほどの絶望をもたらすか、想像できるでしょうか。

身体の自由は憲法で保障されている重要な権利です。会いたい人に会いに行くことも、街を散歩することも、仕事をすることも、身体の自由があってはじめて実現することです。

しかし、現在の日本では、身体拘束が簡単に認められています。特に、罪を認めなかったり、黙秘をしていると、かなりの確率で拘束され続けます。自白が自らの身体の解放の条件とされているようなこの取り扱いは、「人質司法」と呼ばれています。

この「人質司法」は世界的にも稀で、自由主義国家では日本だけとされています。国連の自由権規約委員会や国際NGOのヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチからも、重大な人権侵害として批判されています。

この訴訟は、「人質司法」を許容する刑事訴訟法の規定の違憲性を訴え、人質司法に終止符を打つことを目指しています。

提訴会見の様子

「人質司法」

「人質司法」とは?

現在の日本では、罪を認めない人については、証拠を隠したり、逃げたりなどする可能性があることを理由として、逮捕後の勾留が認められたり、起訴後も保釈が認められなかったりして、結果として長期間にわたって身体拘束されてしまうという運用がなされています。

加えて、身体拘束だけでなく、家族や友人など、外部との交流がおよそ禁止される措置も講じられる場合があります。

「人質司法」は当たり前?

「悪いことをしたから逮捕・起訴がされたのでは」「逮捕されるような人は閉じ込めておくべきじゃないか」と、人質司法を当たり前のものと考えている人もいるかもしれません。

しかし、日本の刑事手続きには、裁判を経て、判決によって有罪と決まるまでは、その人は有罪と扱ってはいけない「無罪推定の原則」という大切な原則があります。逮捕や勾留、起訴をされた時点では、その人はまだ有罪ではないのです。

例え罪を犯した人であっても、無罪推定の原則のもとまだ有罪と決まったわけではありませんから、一般の人と同じように身体の自由が保障されるべきことに変わりはありません。

さらに、いまだに冤罪事件はなくなっておらず、罪を犯していなくても、誰でも逮捕・勾留される可能性はあります。長期間の身体拘束を受け、「罪を認めてしまって、早く外に出たい」そう思ってしまうことに無理はありません。

人質司法を生み出す刑事訴訟法の規定

被疑者・被告人に対する身体拘束は、直接的には勾留に基づき行われ、起訴後に保釈を認めないことによってその状態が維持されています。

勾留は検察官によって、保釈は被告人によって、それぞれ裁判官に対して請求され、裁判官が「罪証隠滅をすると疑うに足りる相当な理由」の有無等を審査し、勾留・保釈を認めるかの判断をする、という仕組みになっています。

すなわち、逮捕されたからといって身体拘束が正当化されるわけではなく、「罪証隠滅をすると疑うに足りる相当な理由」等が認められてはじめて、身体拘束は正当化されるのです。

しかし、現在の実務では、「罪証隠滅を疑うに足りる相当な理由」という要件が極めて抽象的なおそれをもとに認められ、簡単に身体拘束が行われる運用となっています。

また、手続保障にも憲法上の問題があります。なぜ勾留されるのか、具体的な理由が本人には明らかにされず、反論の機会もありません。検察の主張と被告人の反論によって当事者の対等を実現するという対審構造も確保されていません。

この訴訟は、これらの刑事訴訟法の規定が憲法に反することを訴える訴訟です。

訴訟にいたるまでの経緯

原告らが受けた身体拘束

この訴訟では、4名の人質司法の被害者が原告となっています。

一人目の原告の浅沼さんは、強制わいせつ罪の嫌疑で逮捕され、暴行罪で起訴され、合計3ヶ月半にわたって勾留された後、最終的に無罪判決を受けました。

この間浅沼さんは、既に証拠収集が十分にされていること、被害者との接触可能性がないことを理由に身体拘束からの解放を繰り返し求めましたが、いずれも認められませんでした。

二人目の原告の柴田さんは、覚せい剤取締法違反で逮捕・起訴され、有罪判決を受けて服役しています。勾留されている間、2回にわたり保釈を求めましたが、認められませんでした。

三人目の原告の天野さんは、詐欺被疑事件について逮捕・起訴されました。保釈を求めましたが、認められませんでした。天野さんは、2018年の逮捕から2025年3月現在まで、6年以上にわたり勾留されています。

四人目の原告の盛本さんは、不同意わいせつ致傷事件で逮捕・起訴され、2回目の保釈請求が認められて保釈されるまで、約4ヶ月にわたって勾留された後、一審において無罪判決を受けました。

提訴会見に臨む原告の浅沼さん

人質司法による被害

原告たちは身体拘束によって、心身に重大な被害を受けました。それまでの社会生活の多くが壊されてしまいました。

例えば浅沼さんは、自らが代表を務める団体のイベントが延期に追い込まれたり、通っていた医療機関で十分な治療を受けられなくなりました。また、盛本さんは、逮捕前に内定を得ていた転職先への就職が不可能となりました。

人質司法による被害は、長期間の身体拘束そのものだけで十分につらいものです。それに加え、上記のように、身体の自由が制約されることに伴って、社会活動ができなかったり、健康上の被害を被ったり、仕事を失ったりするなど、社会生活上の大きな不利益を負うことになります。

誰にでも起こりうる「人質司法」

4名の原告は、状況も判決も異なりますが、身体拘束による不利益を強いられた、人質司法の犠牲者であるという点で共通しています。

「人質司法」はニュースの中の出来事なのではなく、普通に生活している一般市民誰にでも起こりうる問題なのです。

裁判の争点

本訴訟では、以下の3点が憲法に反すると主張しています。

1. 抽象的な事情だけで「罪証を隠滅すると疑うに足る相当な理由」を認めていること

憲法は、人身の自由を保障しています。そのうえで、特に刑事手続については、戦前の著しい人権侵害に対する反省に基づき、憲法はより手厚い保障を定めています。

憲法34条

何人も、理由を直ちに告げられ、且つ、直ちに弁護人に依頼する権利を与へられなければ、抑留又は拘禁されない。又、何人も、正当な理由がなければ、拘禁されず、要求があれば、その理由は、直ちに本人及びその弁護人の出席する公開の法廷で示されなければならない。

憲法31条

何人も、法律の定める手続によらなければ、その生命若しくは自由を奪はれ、又はその他の刑罰を科せられない。

刑事訴訟法は当然、この憲法の趣旨を守らなければなりません。勾留や保釈の決定は、被疑者・被告人の人身の自由にかかわる重大な判断です。そのため、人身の自由を制限できるのは例外的な場合に限られ、その判断も慎重に行うべきだといえます。

刑事訴訟法60条1項2号

裁判所は、被告人が罪を犯したことを疑うに足りる相当な理由がある場合で、左の各号の一にあたるときは、これを勾留することができる。

二 被告人が罪証を隠滅すると疑うに足りる相当な理由があるとき。

刑事訴訟法89条4号

保釈の請求があつたときは、次の場合を除いては、これを許さなければならない。

四 被告人が罪証を隠滅すると疑うに足りる相当な理由があるとき。

しかし現実には、罪証を隠滅すると思われる「具体的な事情」が何らあるわけでないのに、単なる「抽象的な事情」のみで「罪証を隠滅すると疑うに足る相当な理由」が判断されています。被疑者・被告人の身体の自由を奪う手段が、例外としてではなく、原則かのようにあまりにも安易に用いられています。。

保釈請求については、裁判官の判断が類型化され、抽象的な理由で却下されています。

2. 反論する機会を与えられず、理由も付されずに自由を奪われること

勾留や保釈の決定は重大な判断です。それにもかかわらず、被疑者・被告人は、検察官がもつ証拠やその主張を知る機会がありません。検察官の主張に対して自分の意見を述べる機会も与えられません。これでは弁護人もなすすべもありません。

また、勾留の決定や保釈請求を却下する決定には、理由が付されなければなりません(刑事訴訟法44条)。しかし、これらの決定には何ら具体的な理由も明示されていないのが実情です。

したがって、勾留や保釈に関わるこれらの手続上の欠陥は、憲法上の要請に反していると考えられます。

3. その他(刑事訴訟法89条1号、3号、81条について)

89条は保釈を認めない条件として、全部で6つ定めています。この訴訟では、上記の4号のほかに、1号と3号の違憲性を争っています。

1号はとても重い法定刑の罪を犯したとして起訴されていることを、3号は常習として重い罪を犯したとして起訴されていることを、保釈却下の条件としています。これらは、このような罪を犯したと検察官に訴えられている被告人は、再犯をしたり逃げる確率が高い、ということを理由としています。しかし、そんな実証的な根拠はありません。むしろ海外の研究では、そのような傾向などないことが明らかにされています。また、起訴の時点ではそもそも検察官からそのように主張されているというだけで、犯罪をしたと決まったわけではありません。検察官の一方的な言い分のみで身体拘束をし続けられることは、無罪推定と真っ向から反します。

81条は接見禁止という処分の要件を定めています。接見禁止になると、弁護人以外との面会が禁止されます。裁判所の運用では、共犯事件や薬物事件、暴力団事件で否認・黙秘していると、ほとんど自動的に接見禁止がつけられてしまいます。長期の勾留に加え、家族や友人とも会えないことにより、被告人は精神的に極めて追い詰められてしまいます。人とコミュニケーションを取ることは、人間にとってとても重要な権利です。このような権利を安易に剥奪する81条の違憲性も訴えています。

社会的意義

複数の被害者が原告となって、人質司法の根拠条文の違憲性を正面から争う民事裁判はこれが初めてとなります。被害者それぞれの個別の事情を超えて、違憲的な運用を許す法律の規定自体に問題があることを明らかにします。

勾留や保釈の条文を安易に適用することの違憲性は、多くの場合刑事手続で争われます。しかし、その手続は公開されず、互いに主張を戦わせる構造ではなく、裁判所の理由も極めて簡潔なものとなっています。

この訴訟は民事訴訟です。口頭弁論が開かれます。互いの主張も判決文も公開されます。どちらの主張に説得力があるか、判決の説明は合理的で常識にかなうものか、市民の判断が可能となります。

ぜひ関心を抱いてください。国の主張や裁判所の判決を常識に照らして検討してください。私たちは、この裁判を通じて自ずと各規定の違憲性が顕になり、人質司法に終止符が打たれることを願っています。

資金の使途

- 訴訟費用: 印紙や切手などの実費費用

- 学者に依頼する意見書費用: 刑事訴訟法学者や憲法学者等の専門家に意見書を執筆していただくことを予定しています。

- 国際比較調査: 海外法制や裁判例の調査などを予定しています。

- 海外の文献や裁判例の翻訳費用: 上記のリサーチには翻訳作業が伴うところ、そのための費用となります。

- 弁護団報酬等: 上記各費用を支出後、もし残高がありましたら、弁護団員の着手金、成功報酬、出張日当等に活用したいと考えています。

担当弁護士のメッセージ

弁護団長 高野 隆 弁護士

マイケル・ジャクソンは未成年者に対するわいせつ容疑で逮捕状が発行されましたが、身柄拘束されることもなく裁判所に出頭し100万ドルの保釈金を積んで帰宅しました。彼はその後も「キング・オブ・ポップ」として活躍を続け、陪審裁判で無罪を言い渡されました。

ファーウェイのCFO孟晩舟はアメリカの金融取引法違反の容疑で身柄引渡要求を受けたカナダで逮捕されましたが、やはり保釈され、その後起訴が取り下げられました。彼女は現在も巨大IT企業のCFO兼副会長として活躍しています。

大谷翔平の元通訳水原一平は、大谷の口座から450万ドルあまりを盗んだとして逮捕されましたが、数時間後に保釈されました。弁護人と検察官の合意によって有罪答弁を行い、4年9ヶ月の拘禁刑に服することになりました。

もしも、彼らが日本で逮捕されたとしたらどうでしょうか?

キング・オブ・ポップも巨大企業のCFOも著名野球選手の専属通訳も、その後数ヶ月いや数年にわたって身柄を拘束され、それまでに築き上げたすべて、職も家族も財産もそして健康も失ってしまったでしょう。

この国では現代文明国の基本的なルールである「公正な裁判によって有罪を宣告されるまでは無罪の者として扱われる権利」が存在しないのです。政府が個人に対する刑事訴追をはじめた途端に、裁判で有罪の宣告を受けるずっと前に、その人は有罪の人間として扱われ、自由も財産も生活も奪われるのです。アリスが迷い込んだ「鏡の国」のように時間が逆流しているのです。

わたしたちは、日本の刑事司法における歪んだ時間軸を正常に戻したいと考えています。

宮村啓太 弁護士

「勾留が辛くて耐えられません。もう認めたいです。」刑事弁護に取り組んでいる弁護士の多くは、依頼者にそう言われたことがあるはずです。依頼者の身体を「人質」にとられる「人質司法」が冤罪の大きな原因になっていることは間違いありません。

この裁判で、何としてでも我が国の「人質司法」に終止符を打ちましょう。

趙 誠峰 弁護士

「罪を認めたら釈放してあげる」「罪を認めないならば釈放しない」

ひょっとすると、私たちの社会の中ではこれが当たり前のこと、正しいこと、常識になってるのかもしれません。

しかしみなさん想像してみてください。もしあなたが、本当に罪を犯していないのに捕まっているとしたら。これほど不条理で、残酷で、非人道的なことはないでしょう。

これ以上冤罪を作り出すことは許されません。人質司法に終止符を打ちましょう。

亀石倫子 弁護士

完全に罪を認めているのに、1年以上勾留され続けた依頼者がいました。自分に対しておこなわれた警察の捜査は違法ではないか?と主張していたからです。早く自由になりたければ捜査のあり方など問題にしないほうがいい。そう言われているかのようでした。

「人質司法」のせいで、明るみに出ず、ただされることのなかった違法捜査がたくさんあるはずです。これも「人質司法」による重大な問題です。

支援者のメッセージ

映画監督 周防正行さん

これまでの冤罪事件を振り返れば、人質司法が冤罪を生む大きな要因の一つであることは明らかだ。にもかかわらず、裁判所は「人質司法と呼ばれる事実はない」と自らの過ちに向き合おうとしない。もはや、裁判所は人権を守る最後の砦どころか、人権を抑圧する最強の国家機関だ。

元厚生労働省事務次官 村木厚子さん

私は郵便不正事件で、164日間勾留されました。当時、「なぜ私は裁判が始まる前から罰を受けているのだろう」とずっと考えていました。閉鎖空間に置かれ、自由もなく、誰とも接触できない日々は心をどんどん弱らせます。「公正な裁判」を実現するために、一日も早く「人質司法」を終わらせてください。

イノセンス・プロジェクト・ジャパン理事/弁護士 川﨑拓也さん

「黙秘をして不利にならないか?」接見室で何度問われたか分からない。もちろん「不利になどならない」と答える。しかし、その後に、弁護人として日本の人質司法について話さなければならない。その残酷な説明の後に、彼は房へと戻り、私は家路につく。そのあまりに大きなギャップに、弁護人としての無力を感じる。抜本的な改革で人質司法を変えなければならない。

会社員(人質司法サバイバー) マーカス・カバゾスさん

As a former victim of the act of Japan’s “hostage justice,” I fully support this movement that is taken against it. The act of “hostage justice” is both unethical and emotionally traumatizing to many who have still not even been proven of a crime. I myself was held for half a year of my life under a false accusation and was expected to confess under this coercive method - a method that no doubt has contributed to the baffling 99% conviction rate in this country which most definitely includes innocent people. Let’s change this, for the greater good.

弁護団の紹介

高野 隆 (高野隆法律事務所)

吉田 京子(高野隆法律事務所)

鵜飼 裕未(高野隆法律事務所)

宮村 啓太(宮村・井桁法律事務所)

井桁 大介(宮村・井桁法律事務所、一般社団法人LEDGE事務局長)

趙 誠峰 (Kollectアーツ法律事務所)

小林 英晃(Kollectアーツ法律事務所)

谷口 太規(弁護士法人東京パブリック法律事務所、一般社団法人LEDGE理事)

志塚 永 (弁護士法人東京パブリック法律事務所)

馬淵 未来(弁護士法人北千住パブリック法律事務所)

安藤 光里(弁護士法人北千住パブリック法律事務所)

齋藤 賢(弁護士法人北千住パブリック法律事務所)

亀石 倫子(法律事務所エクラうめだ、一般社団法人LEDGE代表理事)

戸田 善恭(法律事務所LEDGE)

平岡 百合(後藤・しんゆう法律事務所)

LEDGEについて

本訴訟はLEDGEのサポートを受けています。LEDGEは、特定の公共訴訟を支えるために作られた、各種専門家によるチームです。本訴訟の弁護団の一部はLEDGEのメンバーです。

Introduction

Have you ever imagined a life being arrested, detained, and placed under physical restraint?

You wouldn’t be allowed to go outside. You would have to spend your days in a small room, completely shut off from the outside world. Even when moving within the facility, you would be forced to wear handcuffs and a waist chain. Naturally, you wouldn’t be able to attend school or go to work.

You wouldn’t even be free to move around your room as you please. You couldn’t casually lie down. You wouldn't be allowed to have a mobile phone or a computer. Meal times and contents, how often you can bathe — all of that is predetermined. There’s no door on the toilet. You may not be allowed to take your usual medication. Even receiving treatment for something like a cavity can be difficult.

You also wouldn’t be free to meet with people. The number and length of visits would be very limited. In a small visiting room, a police officer sits right next to you, taking notes. You can’t go see someone — you can only wait and hope someone comes to see you.

This life can continue for up to 23 days before indictment — and after indictment, it can go on indefinitely, until the trial ends. You have no idea when it will be over. Even if you apply for bail, only about 30% of requests are granted.

Can you imagine the despair that comes from being held in indefinite detention, with no end in sight?

The right to personal liberty is a fundamental right guaranteed by the Constitution of Japan. The ability to meet someone you want to see, take a walk through your neighborhood, or go to work — all of these are only possible if your freedom is protected.

Yet, in today’s Japan, physical detention is granted far too easily. In particular, if you do not confess or if you choose to remain silent, there’s a high chance you will remain detained. The way in which your confession becomes a condition for release has come to be known as “hostage justice.”

This system of “hostage justice” is extremely rare globally — Japan is considered the only liberal democracy where it exists. It has been strongly criticized as a serious human rights violation by bodies such as the UN Human Rights Committee and international NGOs like Human Rights Watch.

This lawsuit challenges the constitutionality of the provisions in the Code of Criminal Procedure that permit “hostage justice.” Our goal is to bring an end to this system once and for all.

Press Conference Announcing the Filing of the Lawsuit

"Hostage Justice"

What is "Hostage Justice"?

In Japan, if a person does not admit to the charges against them, they are often detained after arrest — and denied bail even after indictment — on the grounds that they might destroy evidence or flee. As a result, they may end up being held in custody for extended periods of time.

In some cases, this physical detention is accompanied by restrictions that effectively cut off all contact with the outside world, including family and friends.

Is "Hostage Justice" the Norm?

Some people might think, “They must have done something wrong to be arrested or indicted,” or “If someone’s been arrested, they should be kept locked up.” In this way, hostage justice is often accepted as normal or even necessary.

However, Japan’s criminal justice system is built upon a fundamental principle: the “presumption of innocence” — meaning that no one should be treated as guilty until they are found to be guilty at the trial. A person who has been arrested, detained, or indicted is not yet guilty.

Even if someone has committed a crime, until their guilt is proven in court, their right to personal liberty should still be respected, just like anyone else.

Furthermore, wrongful convictions continue to occur in Japan. This means that anyone, even an innocent person, could be arrested or detained. Given the harsh conditions of long-term detention, it’s not hard to understand why someone might feel, “I just want to confess so I can get out.”

Provisions in the Code of Criminal Procedure that allow "Hostage Justice"

The physical custody of suspects and defendants is carried out directly through detention and maintained after indictment by the denial of bail.

In this system, detention is requested by the prosecutor, and bail is requested by the defendant, with both requests submitted to a judge. The judge examines whether there is “probable cause to suspect that the accused may conceal or destroy evidence,” among other factors, and then decides whether to approve detention or bail.

In other words, being arrested does not in itself justify continued detention. Detention is only legitimate when “probable cause to suspect that the accused may conceal or destroy evidence,” or similar grounds, are found to exist.

However, in current practice, this requirement of “probable cause to suspect the concealment or destruction of evidence” is interpreted so broadly and abstractly that detention is granted with alarming ease.

Furthermore, there are also serious constitutional concerns regarding procedural safeguards. The individual is not given a clear explanation of the specific reasons for their detention, nor are they given an opportunity to challenge the basis of the detention.

There is no adversarial structure in place that allows for equality between the parties — the prosecutor's assertions and the defendant's rebuttals are not treated as competing positions in a fair hearing.

This lawsuit challenges the constitutionality of these provisions in the Code of Criminal Procedure.

Background of the Lawsuit

Physical Detention Imposed on Plaintiffs

This lawsuit is brought by four individuals who are victims of “hostage justice.”

The first plaintiff, Mr. Asanuma, was arrested on suspicion of indecency, later indicted on assault charges, and detained for a total of three and a half months before ultimately being acquitted. During this time, Mr. Asanuma repeatedly requested to be released on the grounds that sufficient evidence had already been collected and that there was no risk of contact with the alleged victim, but all of his requests were denied.

The second plaintiff, Mr. Shibata, was arrested and indicted for violating the Stimulants Control Act, and is currently serving a prison sentence. While detained, he applied for bail twice, but both requests were denied.

The third plaintiff, Mr. Amano, was arrested and indicted on charges of fraud. He requested bail but was denied. As of March 2025, Mr. Amano has been in detention for over six years since his arrest in 2018.

The fourth plaintiff, Mr. Morimoto, was arrested and indicted on charges of non-consensual indecency resulting in injury. He was detained for approximately four months before being released on bail after his second request for bail was granted, and he was subsequently acquitted in the first trial.

Mr. Asanuma, One of the Plaintiffs, at the Press Conference

Harms Caused by Hostage Justice

The plaintiffs suffered serious physical and mental harm as a result of their detention, and much of their social lives were destroyed.

For example, Mr. Asanuma was forced to postpone events for the organization he worked as a representative, and he could no longer receive adequate medical treatment at the institution where he had been receiving care. Mr. Morimoto, meanwhile, lost the job offer he had received prior to his arrest.

The harm caused by hostage justice is not limited to the hardship of prolonged detention itself — which is already severe. In addition, as seen in the examples above, restrictions on personal freedom often lead to major setbacks in social life: being unable to participate in society, suffering health consequences, or losing employment. These are serious and lasting disadvantages that accompany the loss of liberty.

"Hostage Justice" Could Happen to Anyone

Although the four plaintiffs have different circumstances and outcomes, they all share one thing in common: they are victims of hostage justice, having suffered the harm of unjust detention.

"Hostage justice" is not only something you hear about in the news; it is a problem that can happen to any ordinary person living their daily lives.

Points in Dispute

We claim that the following three points are unconstitutional:

1. Recognizing “probable cause to suspect that the accused may conceal or destroy evidence” based solely on abstract circumstances

The Constitution of Japan guarantees the right to personal liberty. On top of that, the Constitution particularly provides for protection with regard to criminal proceedings, in response to the serious human rights violations that occurred before the war.

Article 34 of the Constitution

No person shall be arrested or detained without being at once informed of the charges against him or without the immediate privilege of counsel; nor shall he be detained without adequate cause; and upon demand of any person such cause must be immediately shown in open court in his presence and the presence of his counsel.

Article 31 of the Constitution

No person shall be deprived of life or liberty, nor shall any other criminal penalty be imposed, except according to procedure established by law.

The Code of Criminal Procedure must, of course, uphold the spirit and intent of the Constitution. Decisions regarding detention and bail are serious determinations that directly affect the personal liberty of suspects and defendants. For this reason, restrictions on personal liberty must be limited to exceptional circumstances, and such decisions must be made with the utmost care.

Article 60, Paragraph 1, Item 2 of the Code of Criminal Procedure

(i) The court may detain the accused when there is probable cause to suspect that the accused has committed a crime and when:

(ii) there is probable cause to suspect that the accused may conceal or destroy evidence

The request for bail must be granted, except when:

(iv) there is probable cause to suspect that the accused may conceal or destroy evidence

However, in practice, probable cause to suspect that the accused may conceal or destroy evidence is often found based solely on abstract circumstances, without any concrete facts indicating an actual risk of evidence concealment or destruction.

The deprivation of a suspect’s or defendant’s personal liberty — which should be allowed only as an exception — is being applied far too readily, as if it were the rule.

In the case of bail requests, judicial decisions have become formulaic, and are frequently denied based on generalized or abstract reasoning.

2. Being deprived of liberty without the opportunity to respond or without stated reasons

Decisions on detention and bail are serious determinations.

Nevertheless, suspects and defendants are not given any opportunity to know what evidence the prosecutor possesses or the arguments being made. Nor are they given a chance to respond to the prosecutor’s claims. In such circumstances, even defense counsel is left without any effective means to act.

Furthermore, decisions to order detention or deny bail are, by law, required to include reasons (Article 44 of the Code of Criminal Procedure). However, in practice, such decisions almost never provide any concrete reasoning.

These procedural deficiencies in the handling of detention and bail decisions are in clear violation of constitutional guarantees.

3. Other issues (Concerning Article 89, Items 1 and 3, and Article 81 of the Code of Criminal Procedure)

Article 89 stipulates six conditions under which bail must not be granted. In this lawsuit, in addition to challenging the constitutionality of Item 4, we also challenge the constitutionality of Items 1 and 3.

Item 1 concerns cases where the accused is indicted for a crime punishable by a particularly severe statutory penalty.

Item 3 concerns cases where the accused is indicted for a serious offense allegedly committed habitually.

Both provisions justify denying bail based on the assumption that defendants charged with such offenses are more likely to reoffend or flee. However, there is no empirical basis for this assumption. In fact, international research has shown that such patterns do not exist.

Moreover, at the indictment stage, these are merely allegations made by the prosecutor — no determination of guilt has been made. Continuing to detain someone based solely on one-sided claims by the prosecutor stands in direct opposition to the presumption of innocence.

Article 81 of the Code of Criminal Procedure stipulates the requirements for the disposition of a no-contact order. When such a restriction is imposed, the accused is prohibited from meeting with anyone other than their lawyer. In practice, courts routinely impose these restrictions in co-defendant cases, drug-related offenses, and organized crime cases, particularly when the accused denies the charges or remains silent. These restrictions are often applied automatically.

When a ban on visits is imposed, the defendant is prohibited from meeting with anyone other than his or her lawyer. In court practice, if a defendant denies the allegations or remains silent in cases of complicity, drug, or organized crime, the no-contact order is almost automatically imposed.

In addition to long-term detention, being cut off from family and friends places enormous psychological pressure on the accused. The ability to communicate with others is a fundamental human right. This lawsuit also challenges the constitutionality of Article 81, which enables such severe restrictions on communication to be imposed far too easily.

Social Significance

This is the first civil lawsuit in which multiple victims have come forward as plaintiffs to directly challenge the constitutionality of the legal provisions underpinning “hostage justice.” The case aims to go beyond the individual circumstances of each victim and expose the fundamental problems in the very laws that allow for such unconstitutional practices.

The constitutionality of how detention and bail provisions are applied with minimal scrutiny is often challenged in criminal proceedings. However, those proceedings are not public, lack an adversarial structure, and the courts typically provide only minimal reasoning.

This, however, is a civil lawsuit. Public hearings will be held. Both the arguments and the final judgment will be made public. This will allow citizens to judge for themselves which side’s claims are more persuasive, and whether the court’s reasoning is sound and in line with common sense.

We invite you to pay close attention to this case. Examine the government’s claims and the court’s rulings through the lens of common sense and reason. We hope this lawsuit will shed light on the unconstitutionality of these provisions — and ultimately bring an end to hostage justice.

Use of Donations

- Litigation expenses: Actual expenses for stamps, photocopies, etc.

- Opinion writing expenses for scholars: We plan to commission written opinions from experts such as scholars in criminal procedure law and constitutional law.

- International comparative research: We plan to conduct research into foreign legal systems and court cases.

- Translation expenses: This refers to the cost of translating materials necessary for the research above.

- Legal service fees etc.: If there is any remaining balance after covering the above expenses, we plan to use it for attorney retainers, success fees, travel allowances, and other related costs.

Message from Attorneys

Takashi Takano, Lead Counsel, Attorney at Law

Michael Jackson was issued an arrest warrant on charges of indecency involving a minor. However, he was never taken into custody; instead, he voluntarily appeared in court, posted bail in the amount of $1 million, and returned home. He continued to thrive as the “King of Pop” and was ultimately acquitted by a jury.

Huawei’s CFO, Meng Wanzhou, was arrested in Canada following a U.S. extradition request on charges of violating American financial regulations. Yet, she was granted bail, and the charges were later dropped. Today, she continues to serve as the CFO and Deputy Chair of one of the world’s largest technology companies.

Shohei Ohtani’s former interpreter, Ippei Mizuhara, was arrested on charges of stealing over $4.5 million from Ohtani’s account, but was released on bail within hours. He later entered into a guilty plea with the prosecution and was sentenced to four years and nine months of imprisonment.

Now, imagine if these individuals had been arrested in Japan. The King of Pop, the CFO of a global corporation, and a high-profile baseball interpreter—each of them would have been detained for months, if not years. In that time, they would have lost everything they had built: their careers, their families, their assets, and even their health.

In this country, the fundamental principle of modern civilized nations—the right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty in a fair trial—simply does not exist. The moment the government initiates a criminal prosecution against an individual, even long before a guilty verdict is rendered in court, that person is already treated as guilty and stripped of their freedom, property, and livelihood. Time is flowing in reverse, just like Alice wandering into Through the Looking-Glass.

We seek to correct the distorted flow of time in Japan’s criminal justice system and restore it to its proper course.

Keita Miyamura, Attorney at Law

“Detention is so hard, I feel like confessing just to make it stop.” Many lawyers working in criminal defense have likely heard these words from their clients. There’s no doubt that “hostage justice,” where a person’s body is essentially taken “hostage,” is a major cause of wrongful convictions.

Through this lawsuit, let's do whatever it takes to put an end to “hostage justice” in our country.

Seiho Cho, Attorney at Law

“If you plead guilty, I’ll release you.” “If you don’t plead guilty, I won’t release you.”

Perhaps in our society, this has become something normal, accepted, even common sense.e

But just imagine: what if you were arrested for something you truly didn’t commit? Nothing could be more absurd, cruel, and inhumane.

We must not allow any more wrongful convictions. It’s time to put an end to hostage justice.

Michiko Kameishi, Attorney at Law

One of my clients continued to be detained for over a year, despite fully admitting to his crime. This was because he insisted that the police investigation conducted on him was illegal. It felt as if he was being told: “If you want to be released, you should not question the way the investigation was carried out.”

Because of the “hostage justice” system, there must be many illegal investigations that never come to light and are never rectified. This is another serious issue caused by “hostage justice.”

Message from Supporter

Masayuki Suo, Filmmaker

Looking back at past wrongful conviction cases, it’s clear that hostage justice is one of the major factors behind them. And yet, the courts continue to deny responsibility, claiming that “there is no such thing as hostage justice.” At this point, the judiciary is no longer the last stronghold for protecting human rights — it has become the most powerful state institution for suppressing them.

Takuya Kawasaki, Director of Innocence Project Japan / Attorney at Law

“Won’t remaining silent put me at a disadvantage?” I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve been asked that question in the meeting room. Of course, I answer, “No, it won’t put you at a disadvantage.” But after that, I have to explain Japan’s system of hostage justice as their criminal defense attorney. After that cruel explanation, he returns to his cell, and I head home. The immense gap between our two worlds makes me feel powerless as a lawyer. We need to dismantle the system of hostage justice entirely.

Marcus Cavazos, Office Worker (Survivor of hostage justice system

As a former victim of the act of Japan’s “hostage justice,” I fully support this movement that is taken against it. The act of “hostage justice” is both unethical and emotionally traumatizing to many who have still not even been proven of a crime. I myself was held for half a year of my life under a false accusation and was expected to confess under this coercive method - a method that no doubt has contributed to the baffling 99% conviction rate in this country which most definitely includes innocent people. Let’s change this, for the greater good.

Legal Counsel Team

Takano Takashi (Takano Law Office)

Kyoko Yoshida (Takano Law Office)

Hiromi Ukai (Takano Law Office)

Keita Miyamura (Miyamura and Igeta Law Offices)

Daisuke Igeta (Miyamura & Igeta Law Offices / Secretary-General, LEDGE)

Seiho Cho (Kollect Arts Law Office)

Eikou Kobayashi (Kollect Arts Law Office)

Motoki Taniguchi (Tokyo Public Law Office / Executive Director, LEDGE)

Hisashi Shizuka (Tokyo Public Law Office)

Miku Mabuchi (Kitasenjyu Public Law Office)

Hikari Ando (Kitasenjyu Public Law Office)

Ken Saitoh (Kitasenjyu Public Law Office)

Michiko Kameishi (Law Office Eclat Umeda / President, LEDGE)

Yoshitaka Toda (Law Office LEDGE)

Yuri Hiraoka(Shin-Yu Law Office)

About LEDGE

This lawsuit is supported by LEDGE, a collective of professionals dedicated to promoting human rights and social change in Japan through strategic litigation. Some of the lawyers in this lawsuit are members of LEDGE.

人質司法の元凶となっている、刑訴法60条1項2号、89条4号などが違憲無効であることを訴え、人質司法に終止符を!訴訟を提訴しています。

高野 隆 (高野隆法律事務所)

吉田 京子(同)

鵜飼 裕未(同)

宮村 啓太(宮村・井桁法律事務所)

井桁 大介(宮村・井桁法律事務所、一般社団法人LEDGE事務局長)

趙 誠峰 (Kollectアーツ法律事務所)

小林 英晃(同)

谷口 太規(弁護士法人東京パブリック法律事務所、一般社団法人LEDGE理事)

志塚 永 (弁護士法人東京パブリック法律事務所)

馬淵 未来(弁護士法人北千住パブリック法律事務所)

安藤 光里(同)

齋藤 賢(同)

亀石 倫子(法律事務所エクラうめだ、一般社団法人LEDGE代表理事)

戸田 善恭(法律事務所LEDGE)

平岡 百合(後藤・しんゆう法律事務所)

関連コラム

-

2025. 7. 21

あなたにおすすめのケース Recommended case for you

- 外国にルーツを持つ人々 Immigrants/Refugees/Foreign residents in Japan

- ジェンダー・セクシュアリティ Gender/Sexuality

- 医療・福祉・障がい Healthcare/Welfare/Disability

- 働き方 Labor Rights

- 刑事司法 Criminal Justice

- 公正な手続 Procedural Justice

- 情報公開 Information Disclosure

- 政治参加・表現の自由 Democracy/Freedom of Expression

- 環境・災害 Environment/Natural Disasters

- 沖縄 Okinawa

- 個人情報・プライバシー Personal information/Privacy

- アーカイブ Archive

- 全てのケース ALL