「鳥は空に魚は水に人は社会に」訴訟 Psychiatric State Compensation Litigation

精神病院に閉じ込められたまま人生の大部分を過ごす人たちが多くいます。精神障害を持つ人も地域で暮らせるようにという世界の潮流に逆行した日本の精神医療は、国際的にも大きな批判を浴びています。この訴訟は、日本の悲惨な精神医療を長年にわたり放置してきた政府の不作為責任を問い、国家賠償請求を行うものです。私たちは、この訴訟を通じて、病院中心に偏った精神医療から地域精神医療への転換が行われることを目指します。 Many people spend most of their lives confined in psychiatric hospitals. Japan's mental health care has gone against the global trend of allowing people with mental disorders to live in the community, and has been criticized internationally. This lawsuit seeks to hold the government responsible for its inaction for years in neglecting the deplorable state of mental health care in Japan, and to seek compensation from the state. Through this lawsuit, we aim to see a shift from hospital-centered mental health care to community mental health care.

東京地裁の敗訴判決から、東京高裁の控訴審へ

From the loss in the Tokyo District Court to the appeal in the Tokyo High Court

2025/7/2 16:49

1.はじめに

精神医療国家賠償請求訴訟(以下「精神国賠」と記します)では、裁判所の法廷を舞台に精神医療に係る様々な問題が問われてきました。ここでは、東京地裁判決後から控訴審開始に至る経過を報告します。

2.東京地裁における敗訴判決

精神国賠は2020年9月30日の提訴以来、ちょうど丸4年後の2024年10月1日に東京地裁における第一審判決が出ました。

地裁判決では、原告の入院形態その他の事実関係と、原告への権利侵害との因果関係については、被告国側の主張を全面的に採用し、原告固有の事情によるものとして国家賠償法上の請求を棄却しました。それ以外の争点については、検討するまでもなく原告の請求には理由がないとして、争点になっていた日本の強制入院制度や精神医療政策に係る一切の判断を避けました。想定以上の不公正で不誠実な不当判決でした。

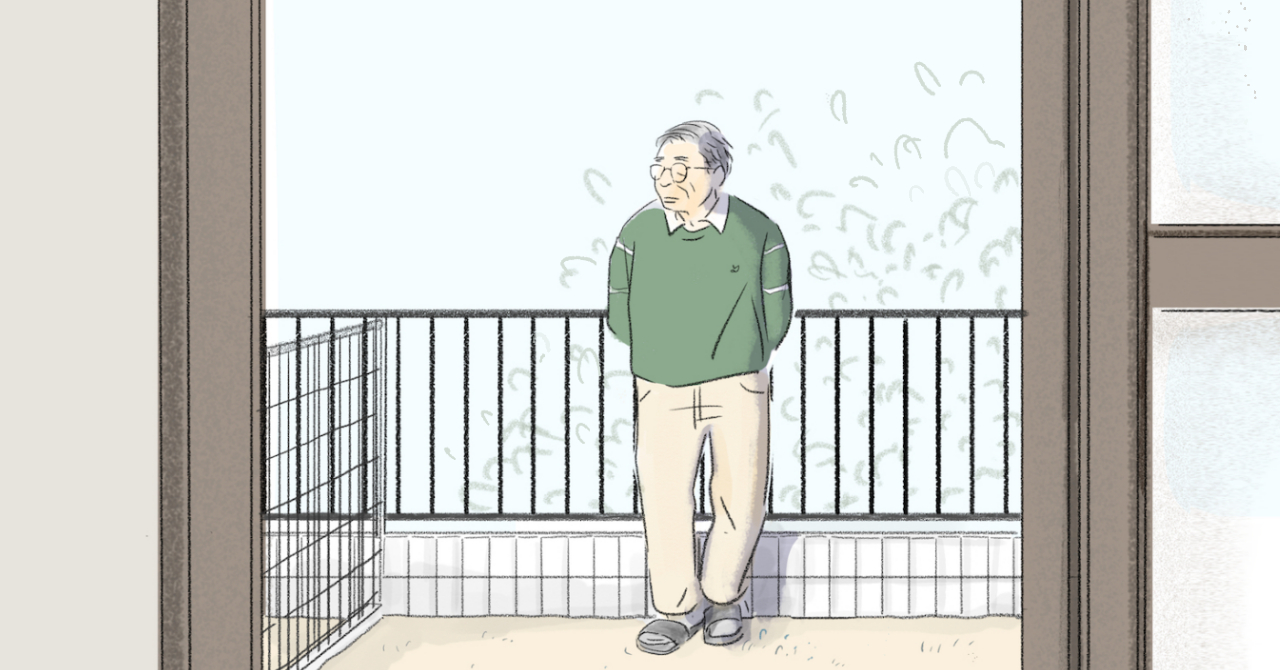

判決報告会には、163名の方が参加されました。原告の伊藤時男さんは、「訴えが棄却され、不当判決だと思っています。社会的入院や施設症の人は未だに苦しんでいます。あの人たちに合わせる顔がない。国の責任を問い、最後まで、最高裁まで控訴して戦うつもりです」と挨拶しました。

判決に立ち会った参加者が最も違和感を感じ怒ったのは、判決文中の「公知の事実」という文言でした。厳格に法を適用すべき裁判所ですら、精神障害者に対する強制入院の必要性は「公知の事実」と断じ、当たり前という感覚で済ませています。この日本社会における精神障害者に対する人権感覚の鈍麻は、長年にわたる国策により作り出されてきたものです。裁判官を含む司法関係者とて、その例外ではないことを地裁判決は明白に示しました。狭い山道を縫って進むような精神国賠の裁判の難しさも映し出しているといえます。

3.控訴理由書の内容

東京地裁において原告は敗訴しましたが、本訴訟はそれで終わったわけではありません。原告の伊藤さんの意思に沿い、2024年10月11月に東京高裁に控訴を申立て受理されました。

10月29日付で提出した控訴理由書においては、原告個人にすべての問題を帰した東京地裁の原判決の誤りと不当性として以下を5点を挙げています。

①精神衛生法等の制度を無視して控訴人の入院形態を強制入院(同意入院等)と認定しなかった誤り

②控訴人の入院形態に関する不十分な審理

③長期入院の原因をごく一時期にみられた控訴人の症状に言及した不当性

④長期入院の原因を控訴人の家族が退院に消極的態度であるとした不当性

⑤長期入院の原因を控訴人が救済措置を求めなかったことにあるとした不当性

また、控訴人の入院が長期化した原因として、⑥長期入院によって退院意欲は奪われること、⑦控訴人自身の意欲の減退により国際法律家委員会が指摘するような入院経過を辿っていること、の2点を挙げました。

さらに、控訴理由書の提出にあたっては、精神国賠研の専門委員会が改めて伊藤さんの入院時の診療録や看護記録の記載内容を精査し、長期入院者が施設症化していく過程を証拠資料として示すとともに、専門職の意見書を追加添付して補強を図っています。

4.国側の答弁書

控訴理由書に対して、被控訴人の国側は2025年1月20日付で「答弁書」を提出しました。被控訴人の主張を示すと、以下の通りです。

①控訴人の入院形態が同意入院等であったとする控訴人の主張は理由がない

②控訴人の入院形態についての審理不尽の違法はない

③国会議員又は厚生大臣等の不作為によって控訴人が長期入院を強いられたと認めることはできないとする原判決の判示に誤りはない

④本人の利益を守るために、本人の同意がなくても入院が必要になる場合があり得るとの原判決の判示は正当である

⑤控訴人の家族が退院に消極的な意向を示したことにより、控訴人の退院について家族との調整ができず、退院の手続が採られなかった可能性があるとの原判決の判示に誤りはない

⑥救済措置に係る控訴人の主張は理由がない

⑦入院形態不明者を作り出した国の責任に係る控訴人の追加主張は理由がない

したがって、「控訴人の主張はいずれも理由がなく、控訴人の請求を棄却した原判決の判断は正当であるから、本件控訴は速やかに棄却されるべき」と結論づけています。

いろいろ批判したい点はありますが、一点、国側の主張で理解に苦しむところがあります。伊藤さんが職員に対して「退院したいんです」等の発言をしていることに対して、国側は「診療録の記載からは、控訴人が退院に向けた準備を進めたい旨の希望を述べた事実が認められるにすぎず、これをもって、精神衛生法等の規定に即した退院の申出とみることは困難である」し「強制入院であったと認めることも困難である」としています。

最新の『五訂精神保健福祉法詳解』を見ても、退院を申し出る相手方は病院の職員であれば誰でもよく、書面でも口頭でも構わないとされています。入院患者が「退院したい」と述べた際に、「退院申出」ではなく「退院準備の希望」であると判断される線引きはどのように引かれるのでしょうか。退院を求めた患者に対する病院の対応や裁判で、この恣意的な解釈が悪しき判例として横行することを危惧します。

5.控訴人意見陳述

2月3日の控訴審第1回口頭弁論では、控訴人の伊藤時男さんが意見陳述を行いました。

冒頭で伊藤さんは「東京地方裁判所の裁判官は、私が40年入院したのは病気や家族のせいだから仕方がないと言いました。また、私自身が入院を選択していたから長期入院も仕方がないとも言いました。精神障害のある人は、病院で暮らすのが当たり前だと言われているようで、とてもショックでした」と述べました。

入院が長引いたのは本人の病状のためとされたことに対しては、「東京地方裁判所の裁判官は、調子がいいときのことは全く触れず、調子の悪いときばかりを取上げました。精神疾患があると、調子の悪いときのことばかりに注目されてしまい、まるで、いつも問題行動を起こすような人、というような偏見の目で見られてしまいます。東京地方裁判所の裁判官は、同じように、そのような偏見の目で私を見ているのだと感じ、とても残念に思います」と述べました。

また、家族が消極的であれば退院できなくても仕方ないという先入観に対しては、「退院が私自身の退院のことなのに、家族の意見で決められてしまうのです。裁判所は、このような理不尽なことを正しいと考えているのでしょうか。このような理不尽なことがまかりとおってしまうことを、恐ろしく思います」と述べました。

さらに、長期入院は自身の選択によるものという判決に対しては、「誰が、好き好んで、このような精神病院での生活を選ぶでしょう」と問い掛け、「私は、何十年も精神病院で入院しているうちに、退院したって、手に職もないし仕事をすることもできなければ家もないので、社会に出ても役に立たない、社会でやっていく自信がないという気持ちになっていました。ですから、尋問のときに、入院当時、入院している方が楽だという気持ちがあったか?と聞かれ、そういうのもあったと答えました。 しかし、入院を自分で選んだという気持ちは少しもありませんでした」と、被告国側の反対尋問への返答が曲解されたことに抗議しました。

そして、最後に伊藤さんは以下のように法廷で裁判官に訴えました。「精神疾患があると、閉じ込められても仕方がないのでしょうか。精神疾患があると、家族のいうことをきかないといけないのでしょうか。何十年も入院させられ退院できなかったことは、自信がなくなった私のせいなのでしょうか。私と同じような人はたくさんいます。退院できないことを嘆いて自ら死を選んだ入院患者さんも見てきました。それは決して精神疾患のせいではありません。この国の精神病院のしくみがどれだけおかしなものであるか、改めて考えていただきたいです」。

傍聴席からは思わず拍手する人が出ました。静粛が原則の法廷ですが、伊藤さんを応援する多くの方の気持ちを表すものでした。

6.おわりに

控訴審は2025年2月3日に始まったばかりですが、新たなステージに移りました。控訴審では一審の原判決を覆す立証が求められ、厳しい道のりが想定されます。

精神国賠の裁判を傍聴していると、この国特有の精神医療に係る特異な論理が横行していることがよくわかります。改めて呉秀三の「この国に生まれたるの不幸」が、なおもこの国で繰り返されていることを痛感します。精神国賠の控訴審の成り行きを、皆さまに見守っていただけることを願っています。

古屋龍太「東京地裁の敗訴判決から東京高裁の控訴審へ」おりふれ通信,No.441;1-3, 2025年3月発行より一部転載

1. Introduction

In the lawsuit seeking state compensation for mental health care (hereafter referred to as "State Compensation for Mental Health Care"), various issues related to mental health care have been put to the test in court. Here, we report on the progress from the Tokyo District Court ruling to the start of the appeal hearing.

2. Losing the case in the Tokyo District Court

The first instance ruling on the mental health compensation lawsuit was handed down by the Tokyo District Court on October 1, 2024, exactly four years after it was filed on September 30, 2020.

The district court's ruling fully accepted the defendant's arguments regarding the causal relationship between the plaintiff's hospitalization and other factual circumstances and the violation of his rights, and dismissed his claim under the State Compensation Act as being due to circumstances specific to the plaintiff. As for the other issues, the court ruled that the plaintiff's claims were without merit without even needing to be examined, and avoided any judgment on the issues at stake, namely Japan's forced hospitalization system and mental health care policy. This was an unjust ruling that was more unfair, dishonest, and unjust than we had anticipated.

163 people attended the verdict announcement meeting. Plaintiff Tokio Ito said in his opening remarks, "My lawsuit was dismissed. I believe this is an unjust verdict. People who are socially hospitalized or institutionalized are still suffering. I cannot face those people. I will hold the government responsible and fight to the end, appealing all the way to the Supreme Court."

What made the participants who attended the ruling feel the most uncomfortable and angry was the phrase "publicly known fact" in the ruling. Even a court that should strictly apply the law has declared the necessity of compulsory hospitalization of the mentally ill to be a "publicly known fact" and has dismissed it as something that should be taken for granted. This dulling of the sense of human rights towards the mentally ill in Japanese society has been created by national policy over many years. The district court ruling made it clear that those involved in the judicial system, including judges, are no exception. It also reflects the difficulty of navigating a narrow mountain path in a trial for mental health compensation.

3. Contents of the Statement of Reasons for Appeal

Although the plaintiff lost the case at the Tokyo District Court, the lawsuit is not over. In accordance with the plaintiff, Mr. Ito's wishes, he filed an appeal with the Tokyo High Court in October 2024, and the appeal was accepted.

In the appeal statement submitted on October 29, the plaintiffs listed the following five points as errors and injustices in the original Tokyo District Court ruling, which attributed all issues to the individual plaintiffs.

① The error of ignoring the Mental Health Act and other laws and not determining that the appellant's hospitalization was compulsory (consent-based hospitalization, etc.)

2) Insufficient investigation into the appellant’s hospitalization status

3) The injustice of citing the appellant's symptoms, which were only observed during a short period of time, as the cause of his long-term hospitalization

④ The injustice of attributing the appellant's long-term hospitalization to his family's reluctance to discharge him from the hospital

⑤ The injustice of the appellant's failure to seek relief measures as the cause of his long-term hospitalization

The court also cited two reasons for the appellant's prolonged hospitalization: (6) prolonged hospitalization removes the desire to leave the hospital, and (7) the appellant's own declining motivation has led to a course of hospitalization in the way that the International Commission of Jurists pointed out.

Furthermore, when submitting the statement of reasons for appeal, the expert committee of the National Institute of Mental Compensation Relief re-examined the contents of Mr. Ito's medical records and nursing records from the time of his hospitalization, and provided evidence of the process by which long-term hospitalized patients become institutionalized, as well as attaching additional opinions from experts to strengthen the evidence.

4. Government's Reply

In response to the Statement of Appeal, the appellee, the State, submitted a "Response" dated January 20, 2025. The appellee's arguments are as follows:

① The appellant's argument that the appellant was admitted by consent is without merit.

② There was no illegality in the lack of fairness in the trial regarding the appellant’s hospitalization status.

3) There is no error in the original judgment that it cannot be recognized that the appellant was forced into long-term hospitalization due to the inaction of Diet members or the Minister of Health, Labor and Welfare.

④ The original ruling that hospitalization may be necessary even without the person's consent in order to protect the person's interests is justified.

⑤ The original judgment's ruling that the appellant's family was reluctant to discharge him from the hospital and therefore it was not possible to coordinate with them regarding the appellant's discharge and that the discharge procedure may not have been carried out is not erroneous.

⑥ The appellant's argument regarding relief measures is without merit.

7) The appellant's additional argument regarding the state's responsibility for creating patients with unknown hospitalization status is without merit.

Therefore, the court concluded that "none of the appellant's arguments are meritless and the original judgment dismissing the appellant's claims is justified, and therefore the appeal should be promptly dismissed."

There are many points I would like to criticize, but there is one point in the government's argument that I find difficult to understand. Regarding Ms. Ito's statements to staff such as "I want to be discharged from the hospital," the government argues that "the medical records merely acknowledge the fact that the appellant expressed a wish to begin preparations for discharge, and it is difficult to view this as a request for discharge in accordance with the provisions of the Mental Health Act, etc." and that "it is also difficult to acknowledge that she was forcibly hospitalized."

Even in the latest "Detailed Commentary on the Mental Health and Welfare Law, 5th Edition," it says that the person making the request to leave the hospital can be any hospital staff member, and that it can be done in writing or verbally. When an inpatient says, "I want to leave the hospital," how is the line drawn to determine whether this is a "request to prepare for discharge" rather than a "request for discharge"? We fear that this arbitrary interpretation will become a bad precedent in hospitals' responses to patients who request discharge and in court cases.

5. Appellant's statement of opinion

At the first oral argument of the appeal trial on February 3rd, appellant Tokio Ito made a statement.

At the beginning of her speech, Ms. Ito said, "The judge at the Tokyo District Court said that it was inevitable that I had been hospitalized for 40 years because of my illness and my family's fault.He also said that it was inevitable that I had been hospitalized for so long because it was my own choice.It seemed like the judge was saying that it was normal for people with mental disorders to live in hospitals, and I was very shocked."

Regarding the fact that his prolonged hospitalization was due to his illness, he said, "The judge at the Tokyo District Court never mentioned the times when I was doing well, and only focused on the times when I was doing badly. When you have a mental illness, people only focus on the times when you're not doing well, and you end up looking at them with prejudice, as if they're always causing trouble. I feel that the judge at the Tokyo District Court is looking at me with the same prejudice, and I feel very disappointed."

Regarding the preconceived notion that it is inevitable that a patient cannot be discharged from hospital if their family is reluctant, she said, "Even though it is my own discharge from hospital, the decision is made based on the opinion of my family. Does the court think that such unreasonable behavior is right? I am horrified that such unreasonable behavior is allowed to continue."

Furthermore, in response to the verdict that her long-term hospitalization was of her own choice, she questioned, "Who would willingly choose to live in a psychiatric hospital like this?" and said, "After being hospitalized for decades in a psychiatric hospital, I began to feel that even if I was released, I would have no skills, no job, and no home, so I would be useless if I went out into society, and I had no confidence that I could function in society. So during the cross-examination I was asked, "At the time I was hospitalized, did you feel that staying hospitalized would be easier?" and I answered that yes, that was part of it. However, I never felt for a moment that I chose to be hospitalized." She protested against the misinterpretation of her responses to the defendant's cross-examination.

Finally, Ito appealed to the judge in court as follows: "Is it inevitable to be locked up if you have a mental illness? Does having a mental illness mean you have to listen to what your family says? Is it my fault that I lost confidence and was hospitalized for decades and unable to leave? There are many people like me. I have seen hospitalized patients who chose to commit suicide out of lamentation over not being able to leave. That is never the fault of a mental illness. I would like you to think again about how strange the system of psychiatric hospitals in this country is."

Some people in the gallery burst into applause. Silence is the rule in the courtroom, but this expressed the feelings of the many people who supported Ito.

6. Conclusion

The appeal trial has just begun on February 3, 2025, but has now entered a new stage. The appeal trial will require proof to overturn the original ruling from the first instance, and is expected to be a tough road.

As I attend the trial for mental health compensation, I can clearly see the unique logic that is unique to this country regarding mental health care. I am once again keenly aware that Wu Shuzo's "misfortune of being born in this country" is still being repeated in this country. I hope that everyone will keep an eye on the progress of the appeal trial for mental health compensation.

Ryuta Furuya, "From the Losing Judgment in the Tokyo District Court to the Appeal in the Tokyo High Court," Orifure Tsushin, No. 441; 1-3, reprinted in part from the March 2025 issue

東京地方裁判所判決に対する声明

Statement regarding the Tokyo District Court ruling

2024/10/3 15:08

精神医療国家賠償請求訴訟(伊藤時男さん裁判)

東京地方裁判所判決に対する声明

2024年10月1日、東京地方裁判所において、伊藤時男さんを原告とする国家賠償請求訴訟(令和2年(ワ)第24587号)の判決が申し渡された。

判決は、原告の国家賠償請求を退けた。判決理由では、裁判の争点となっていた、この国の精神医療法制度に対する評価は一切記されなかった。そして、国の主導した隔離収容政策の歴史的経過に係る憲法判断を避け、踏み込んだ記述は皆無であった。

裁判所は、長期入院の原因を、時男さんの病状が芳しくない一時期のカルテ記載内容を根拠に「原告の病状」によるものとし、国の不作為責任を問うた原告の主張を一蹴した。

特に、判決理由においては「統合失調症などの精神疾患を有する患者については、判断能力自体に不調を来すことがあり、患者本人が適切な判断をすることができず、本人の同意がなくても入院が必要になることがあり得ることは公知の事実というべき事柄」であると断じている。これは、一時的な判断能力の不調を根拠に長期の社会的入院を当然とする、裁判所の精神障害者に対する差別的偏見を示したものといえる。

また、入院の長期化は「入院生活の方が楽だという気持ちになっていた」原告が「入院生活を継続することを自ら選択するに至ったもの」とする被告国側の主張を認め、施設症による自発的意思表明が難しい社会的入院状態にあったという原告の主張を退けた。

さらに、精神医療審査会や人身保護法による「救済の途は当然開かれている」にもかかわらず、原告は「退院等の請求をしたり、弁護士に救済を求めることはなかった」とし、長期入院は「同意入院や任意入院等といった制度の問題であるとも、精神医療政策の問題であるともいうことはできない」としている。この国における精神医療の現実と入院患者の置かれた状況を一顧だにせず、患者個人の自己責任に問題を還元している。

裁判所は「よって、その余の点を検討するまでもなく原告の請求は理由がない」と結論し、原告の請求を棄却した。

2020年9月30日の提訴以来、丸4年、計16回の口頭弁論を経てくだされた判決としては、あまりにも理不尽な中身のない判決と言わざるを得ない。精神科病院内の現実を知らない裁判所の不見識に、ただただ唖然とするしかない。40年にわたって社会的入院を強いられ、人生の大切な時間を失った、時男さんの悲しみと悔しさはいかばかりであろうか。

精神医療国家賠償請求訴訟研究会は、歴史的判決日に立ち会った多くの人々とともに、怒りと悲しみを持ってこの不当判決に強く抗議する。そして、原告の時男さんの意思に沿い、高等裁判所への控訴を今後行うことを表明する。

この国の精神医療を抜本的に変革し、精神疾患を有する方々が名実ともに社会的復権を果たし、「この国に生まれた不幸」が払拭されるその日まで、私たちは粘り強く戦い続けることをここに宣言する。

2024年10月2日

精神医療国家賠償請求訴訟研究会

Lawsuit for State Compensation for Mental Health Care (Tokio Ito Trial)

Statement regarding the Tokyo District Court ruling

On October 1, 2024 , the Tokyo District Court handed down a judgment in the lawsuit seeking state compensation (Reiwa 2 (Wa) No. 24587) filed by plaintiff Tokio Ito.

The ruling dismissed the plaintiffs' claim for state compensation. The reasons for the ruling did not include any evaluation of the country's mental health care legal system, which was the main point of contention in the trial. Furthermore, the ruling avoided a constitutional ruling on the historical course of the state-led segregation and confinement policy, and contained no in-depth description at all.

The court determined that the cause of Tokio's long hospitalization was due to "the plaintiff's medical condition" based on the contents of his medical records from a period when his condition was not good, and dismissed the plaintiff's argument that the government was responsible for its inaction.

In particular, the reasons for the judgment stated that "It is a well-known fact that patients with mental illnesses such as schizophrenia may experience impaired judgment, and may be unable to make appropriate decisions themselves, resulting in the need for hospitalization even without the patient's consent." This shows the court's discriminatory prejudice against mentally disabled people, who are expected to be hospitalized for long periods of time based on a temporary impairment of judgment.

The court also accepted the defendant's argument that the plaintiff's prolonged hospitalization was due to the fact that he "felt that hospitalization would be easier" and "came to the point where he chose to continue his hospitalization of his own accord," and rejected the plaintiff's argument that he was in a socially hospitalized state that made it difficult for him to express his will voluntarily due to institutionalization.

Furthermore, although "the path to relief is obviously open" through the Psychiatric Review Board and the Habeas Corpus Act, the plaintiff "never requested discharge or sought relief from a lawyer," and the long-term hospitalization "cannot be said to be a problem with the system, such as consensual hospitalization or voluntary hospitalization, nor a problem with psychiatric care policy." Without even considering the reality of psychiatric care in this country and the situation hospitalized patients find themselves in, the problem is reduced to the personal responsibility of the individual patient.

The court concluded, "Therefore, without even considering the further points, the plaintiff's claim is without merit," and dismissed the plaintiff's claim.

Considering that the ruling was handed down over four full years since the lawsuit was filed on September 30, 2020 , and that a total of 16 oral arguments had been held, this ruling can only be described as extremely unreasonable and empty of substance. One can only be stunned by the lack of insight of a court that does not know the reality inside a psychiatric hospital. How much sadness and regret must Tokio have felt, having been forced into social hospitalization for 40 years and losing precious time of his life?

The Research Group for Psychiatric State Compensation Lawsuits, together with the many people who were present on the historic day of the ruling, strongly protests this unjust ruling with anger and sadness. We also declare that, in accordance with the wishes of the plaintiff, Tokio, we will appeal to the High Court.

We hereby declare that we will continue to fight tenaciously until the day we achieve fundamental reform of mental health care in this country, until those with mental illnesses are truly and truly restored to society, and until the day when the "misfortune of being born in this country" is erased.

October 2 , 2024

Research Group on State Compensation Lawsuits for Mental Health Care

第15回口頭弁論(当事者尋問)

15th Oral Argument (Parties Examination)

2024/9/25 11:25

伊藤原告、当事者尋問に堂々と ドキュメント2.27

2024 年2月27日、第15回口頭弁論が行なわれました。今回は、それまでの開廷10 分前の入廷とは異なり、30 分前に103号法廷のドアが開きました。そしてすぐに傍聴席は満席になりました。満席後に到着され入廷できなかった方は、商工会館に移動 してもらい、ミニ交流会を行なっていました。

原告側弁護団は7名、被告国側代理人は4名が出席せきしました。15 時、定刻に開廷。さっそく伊藤時男さんに対する当事者尋問が行なわれました。 時男さんは長谷 川弁護団長との一問一答で、発病から入院に至る経過、福島への転院、精神科病院での入院生活を語りました。

約50分の主尋問の後、被告国側から15 分の反対尋問が行なわれ、その後さらに原告代理人弁護士が追加質問をしました。

次回の裁判期日を決め、16 時15 分には閉廷となりました。 次回口頭弁論は 6 月18日火曜日、15時103法廷と決まりました。また、追加する準備書面などがあれば、6月3日までに全て提出するように、という裁判長の指示がありました。原告・被告双方の主張を出揃わせ、次回口頭弁論で結審になるもよう。

その後、商工会館に移動し、報告会が行なわれました。報告会終了後はその同じ会場で、時男さんの『かごの鳥』出版記念&誕生会が開かれました。

当事者尋問について

原告側尋問

●入院することとなった経緯

●精神科病院における入院生活・入院治療の実態

●伊藤さん自身が入院形態についてどういう認識をもっていたのか

●退院の申し出でをどういうふうにしていたのか

●それに対して病院、ご家族との関係はどうだったのか

●法改正によっても状況は変わらなかったのか

●長期入院によって施設症になったこと

●退院の経緯

以上の内容に沿って尋問がなされました。

被告反対尋問

●入院中も自由に過ごしていたのではないか。自らの意思で入院し、その生活を謳歌していたのではないか。ということを聞き出そうとしていました。

争点1 事実認定について

証拠として提出された精神科病院のカルテには入院形態に関する記載がありません。 一般にカルテのトップに記載されている

〇〇年〇月〇日~●●年●月●日 医療保 護入院

▲▲年▲月▲日~★★年★月★日 入院形態変更・任意入院

保護者名 〇×△□ といった記載がないのです。

したがって、伊藤さんが強制的に入院させられていたのかどうかということが争点の一つにならざるを得ませんでした。

それで被告は

●伊藤さんは入院中もいろんなところに出かけていた。いろんなイベントもあった。 ある程度自由に過ごしていたのでは。

●伊藤さんは任意入院。

●仮に強制入院だったとしても、人権制約は少なかったのではないか。

ということを裁判官に印象づけようと意図したと思われます。

対して原告側は

●最初は、旧制度下の「同意入院」=医療保護入院からスタート。知らないうちに任意入院に替わったが、お父とうさんが亡くなるまではずっと強制入院のまま。伊藤さんの意思で入院しているのではないことを証言してもらいました。

●原告弁護団は、当時の精神衛生法上「同意入院」しかありえず、法改正後も「医療保護入院」であったことを主張しています。

●父親死去後に「任意入院」への切り替えが行なわれたのかもしれませんが、時男さんはそのような説明を受けたことはないと法廷で証言しました。

争点2 施設症について

●伊藤さんは退院を諦めた。

→原告側:長期入院の結果、それによってもたらされた意識。自発的なものではない。

→被告側:伊藤さんは自らの意思で入院しており、入院生活を楽しんでいた。入院を自分で望んでいたではないか。

尋問で明らかになったもの

●入院の経緯:東京の病院で入院

→最初の段階で強制入院だったことは明らか。

●福島に転院した後の病状 転院後も病状が良くなかった

→転院後も医療保護入院であった。

●「自由入院」という言葉を知っているか:知らない

●父親に言われて入院した

→保護者の同意に基づく入院であった。

●精神科病院での入院実態:長期間に渡って院内作業、院外作業をしていた

→入院の必要性がなかったことは明らか。

●退院の申し出をしたか:した

病院:家族がOKなら退院させる

家族:院長がOKなら退院させる

→板挟みになり、事実上退院できない状況が生まれ、退院の意欲が削がれていった。 病院と家族の板挟みの状況が施設症を生み出だしていくという構造を明らかにした

●状況を変えるためには外部からの働きかけが不可欠。外部からの働きかけはあったのか:ない

→医師、看護師、ケースワーカーなどはどんな働きかけをしてくれたのか。

●病院への外部監査はあったか:あったがベッド数を誤魔化すだけだった

●外出はどれ位くらいの頻度で行なったか:年に1、2回

●入院費は誰が払っていたのか:家族が負担

●入院形態の説明はあったか:ない

● 施設症にどうしてなったのか。諦めた理由は何か:(何をやっても変わらない状況に)絶望した

●退院請求制度を知っているか、使ったことはあるか:知らない。使ったことはない→原告:退院請求制度が機能していないことを裁判官に分かってもらうために質問。

→被告:退院請求制度を使ったことがない。使っていたら退院できたかもしれないことを示唆。

●退院の経緯:東日本大震災後に転院した病院で、医師からグループホームを勧められた

→施設症があろうとも、働きかけがあればすぐに退院している。

→国が監督していなかったのが問題。

こうして、「病状も安定しており、働けていたのに、40 年近く退院できなかった」現 実を証言しました。 なお、原告側が求めていた3名の証人尋問は、裁判長により却下されました。

出典元:新井満「伊藤原告、当事者尋問に堂々と ドキュメント2.27」『精神国賠通信』第32号1~3頁、2024年6月1日発行

※元原稿は全文ルビ入りでしたが、転載にあたり再構成し一部の文言を修正しています(古屋)

Plaintiff Ito confidently responds to party questioning Document 2.27

On February 27, 2024, the 15th oral argument took place. This time, unlike the usual 10 minutes before the start of the trial, the doors to Courtroom 103 opened 30 minutes before the trial began. The gallery was soon filled to capacity. Those who arrived after the courtroom was full and were unable to enter the courtroom were moved to the Chamber of Commerce and Industry building for a mini social gathering.

Seven lawyers for the plaintiffs and four lawyers for the defendants were in attendance. The court opened at 3 p.m. as scheduled. The questioning of Tokio Ito began immediately. In a question-and-answer session with the head of the legal team, Mr. Hasegawa, Mr. Ito spoke about the events that led from his onset of illness to his hospitalization, his transfer to Fukushima, and his life in the psychiatric hospital.

After approximately 50 minutes of main questioning, the defendant's side conducted 15 minutes of cross-examination, after which the plaintiff's attorney asked additional questions.

The next trial date was set, and the court adjourned at 4:15 p.m. The next oral argument was scheduled for Tuesday, June 18th, at 3:10 p.m. The presiding judge also instructed that any additional preparatory documents should be submitted by June 3rd. It appears that the next oral argument will conclude the case, with both the plaintiff and defendant presenting their arguments.

Afterwards, the group moved to the Chamber of Commerce and Industry building, where a presentation was held. After the presentation, a publication celebration and birthday party for Tokio-san's "Kago no Tori" was held in the same venue.

Regarding the examination of the parties

Plaintiff's Examination

The circumstances that led to hospitalization

The reality of hospital life and inpatient treatment in psychiatric hospitals

What was Mr. Ito's own understanding of the type of hospitalization he was in?

How did you respond to the request to leave the hospital?

How was your relationship with the hospital and your family?

Did the change in the law not change the situation?

- Becoming institutionalized due to long-term hospitalization

●Discharge history

Questions were asked along the lines of the above.

Cross-examination of the Defendant

●Is it possible that he was able to spend his time freely while he was hospitalized? Was it possible that he was hospitalized of his own volition and was enjoying his life to the fullest? I was trying to find out this.

Point of issue 1: Fact-finding

The psychiatric hospital chart submitted as evidence does not include information about the type of hospitalization.

Hospitalized under medical protection from __/__/__ to __/__/__

▲▲year▲month▲day to ★★year★month★day Change of hospitalization type/voluntary hospitalization

There is no information such as parent's name (〇×△□).

Therefore, one of the points of contention had to be whether or not Mr. Ito had been forcibly hospitalized.

So the defendant

●Even while you were hospitalized, Ito-san went out to many places. There were many events. I guess you had a certain amount of freedom.

●Mr. Ito was hospitalized voluntarily.

●Even if the hospitalization was compulsory, there were probably fewer restrictions on human rights.

It seems likely that they intended to impress upon the judge this fact.

On the other hand, the plaintiff

●At first, it started as "consented hospitalization" under the old system, which is medical protective hospitalization. Without my knowledge, it was changed to voluntary hospitalization, but it remained a compulsory hospitalization until my father passed away. Ito testified that he was not hospitalized of his own will.

●The plaintiff's legal team argues that under the Mental Health Act at the time, only "consensual hospitalization" was possible, and that even after the law was revised, the hospitalization was "medical protective hospitalization."

●It is possible that the hospitalization was switched to "voluntary hospitalization" after his father's death, but Tokio testified in court that he was never informed of this.

Point of issue 2: Institutionalization

●Mr. Ito gave up on being discharged from hospital.

→ Plaintiff: The consciousness was brought about as a result of long-term hospitalization. It was not voluntary.

→ Defendant: Mr. Ito was hospitalized of his own volition and enjoyed his hospital stay. He had wanted to be hospitalized himself.

What emerged from the interrogation

●Hospitalization history: Hospitalized at a hospital in Tokyo

→It was clear from the outset that he was forcibly hospitalized.

●Condition after transfer to Fukushima The patient's condition did not improve even after transfer

→Even after being transferred to another hospital, he remained hospitalized for medical protection.

●Do you know the term "voluntary hospitalization"?: No.

I was hospitalized because my father told me to.

→The patient was hospitalized with the consent of the guardian.

● The reality of hospitalization in a psychiatric hospital: Working inside and outside the hospital for a long period of time

Clearly there was no need for hospitalization.

Did you request to be discharged?: Yes

Hospital: If the family is OK with it, discharge the patient.

Family: If the director is OK with it, I'll discharge him.

→ Caught between a rock and a hard place, the situation created one where the patient could not be discharged, and their desire to leave the hospital was diminished. This clarified the structure in which the situation of being caught between the hospital and the family creates institutionalization.

●In order to change the situation, outside influence is essential. Was there any outside influence?: No

→What kind of efforts did doctors, nurses, case workers, etc. make?

- Were there any external audits of the hospital? Yes, but they only falsified the number of beds.

How often did you go out? Once or twice a year

Who paid the hospital bills? Family members paid for them.

Was there an explanation of the type of hospitalization?: No

- Why did you become institutionalized? Why did you give up? (No matter what you did, the situation would not change.) You felt hopeless.

●Do you know about the discharge request system and have you ever used it?: I don't know. I have never used it. → Plaintiff: This is a question to make the judge understand that the discharge request system is not functioning properly.

→ Defendant: He never used the discharge request system. He suggested that if he had used it, he might have been able to be discharged from hospital.

●Background to discharge from hospital: After the Great East Japan Earthquake, the doctor at the hospital where he was transferred recommended that he live in a group home.

→ Even if they have institutionalized conditions, they are discharged immediately if there is encouragement.

→The problem was that the government did not supervise it.

Thus, he testified about the reality that "although my condition had stabilized and I was able to work, I was unable to leave the hospital for nearly 40 years." The presiding judge rejected the plaintiff's request to call three witnesses.

Source: Mitsuru Arai, "Plaintiff Ito, confident in the party questioning, Document 2.27," "Spiritual Compensation Newsletter," No. 32, pp. 1-3, published June 1, 2024

*The original manuscript was fully written with ruby, but it has been reconstructed and some of the wording has been revised for reprinting (Furuya)

第16回口頭弁論(結審):2024年6月18日

16th Oral Argument (Conclusion): June 18, 2024

2024/9/24 19:35

第16回口頭弁論(結審)のご報告です。

東京は激しい雨でしたが、傍聴席には62名の方に参加いただきました。

裁判自体は、原告・被告双方が提出した最終書面の確認をしただけで結審となりました。

次回判決日が10月1日(火)14時~と告げられ、ほんの3分程で閉廷となりました。

雨の中を移動後の裁判報告会には受付記帳で67名の方に参加いただきました。

Zoomには24名の方に接続いただき、複数名で視聴いただいていた方もいたので、合計99名の方と考えています。

遠隔地からも多くの方々が、結審の成り行きを見守って下さっていて感謝いたします。

報告会は、長谷川弁護士が急用で出席できませんでしたが、まとめていただいた文書を古屋が読み上げる形で報告しました。

以下、その内容を「 」で要約して、古屋の感想も交えてお伝えします。

今回の裁判で提出された書面は、「原告準備書面8」と「被告準備書面(7)」でした。

前回の原告の当事者尋問を踏まえて、原告側は、これまでの主張の整理も行い書面化しました。

しかし、被告国側は、事実レベルの主張のみのとても短いものでした。

◆事実レベルの主張

カルテの記載内容が杜撰なため(あるいは改竄のため)「入院形態」が1つの争点になっています。

原告側は「精神衛生法時代の入院のため同意入院で」「カルテ内容や原告の認識からすれば2003年までは医療保護入院」であることは明らかとしました。

その上で「そもそも入院形態が明確でないことは、国の制度設計の不備に由来するもの」「強制入院の実態には変わりがなく、これによる不利益を原告に追わせるべきではない」としました。

一方で、被告側は「原告の入院形態は立証されていない」としています。

原告が退院できなかった理由が、前回の当事者尋問で繰り返し問われた内容でした。

原告側は、「長年にわたる入院治療は不要であった」と主張しました。

その理由として「自らの症状や状況を客観視できていた」「作業に問題なく従事できていた」「転院後にすぐに退院できた」「退院後問題なく生活している」等を挙げました。

さらに「原告の治療に携わった医師も、カルテ等を精査した精神科医も、長年の入院治療は不要であった」との証言をしていることを挙げました。

これに対して、被告側は、「退院できなかった原因は、国の不作為によるものではない」としています。

退院できなかったのは「原告の病状の可能性」と「家族が退院を認めていなかった」可能性を挙げて、「原告自身が入院しているほうが楽であると考えて、入院継続を選択していた」としました。

(この最後の理由については、時男さんも「ひでえこと言いやがる」と報告会で述べていました)

◆法律等の憲法違反に関して

原告側は、「同意入院、医療保護入院を定めた規定は違憲」「任意入院も真の任意性が担保されておらず違憲」「精神科特例も違憲」と主張しました。

被告側は、これについて今回の書面では一切触れていません。

◆国賠法上の「違法性」について

原告側は、「これまで立法不作為の違憲性は国賠法によって救済がなされてきており、本件でも国賠法上の救済を閉ざすべきではない」としました。

特に「人身の自由という根幹的な人権侵害であり、その権利侵害性は明白」「これを認識しながら、法律を改廃しなかったことは違法」としました。

そして、「人身の自由等の根幹的な人権侵害」は「その前提となる隔離収容政策は国の政策に起因すること」を述べました。

特に「医療保護入院は、多くの民間病院に強制入院の権限を与え」「低医療費・低人件費で病院経営をさせ」「隔離収容政策となることを国が是認していた」としました。

「国がどのような政策をとろうが条理上の責任を負わないとするのであれば、法律で私人に幸福追求権、人身の自由、移動の自由などを制限する権限を与えて国は一切責任を負わないこととなる」とその不当性を述べ、厚生(厚労)大臣は「条理上の作為義務を負う」としました。

その上で、人権侵害を認識しながら、地域医療への政策転換、精神病院に対する指導監督、長期入院を強いられている人に対する救済をしてこなかったことは違法であるとしました。

被告側は、これらの点について、今回の主張書面では一切触れていません。

これまで、立法不作為については、それが違法と評価されるためには、権利侵害が明白である場合など限定的な場面に限られるべきと主張しています。

また、厚生大臣の作為義務についても、条理上の作為義務はその義務や権限が一義的ではないとして、国賠法上の違法性が認めらないと主張しています。

◆参加者の意見

裁判報告会に参加した会場およびZoomの参加者からは、

「被告国側は、事実レベルの争点に集約して逃げている」

「被告国側は、現行法による医療保護入院は適法、合憲と考えているのか」

「これまでの審議会や検討会、国会で真摯に語られてきた反省と総括はどこに行ったのか」

「被告国側は、時男さんの意見陳述にこころ揺さぶられないのか」

等々の意見が述べられました。

◆まとめ

一審判決は、10月1日(火)14時~に出される予定です。

判決までの期間としては、妙に長いなという印象を持ちます。

それがどのような意味を持つのか、現時点ではわかりません。

裁判ですので、「勝訴」か「敗訴」かの二択になる訳ですが、両者の間には相当幅の広いグラデーションがあり得ます。

私たちは、原告の主張について国賠法上の違法性を認める「勝訴判決」を求めています。

しかし、国賠法上の違法性を認めない「敗訴判決」であっても、憲法上の違憲性は認められる場合もあり得ます。

また、憲法上の違憲性等を判断しなかったり、医療保護入院等は憲法上合憲であると判断することもあり得ます。

被告国側が目指しているのは、原告側に事実レベルの立証がないとして、論点に入らず原告の請求を棄却する判決でしょう。

判決に書かれる文言によって、今後の精神医療政策への影響の度合いが変わってきます。

10月1日の判決に向けて、精神国賠研としてこころして準備に取り組まねばと、意を新たにしたところです。

判決の日をどのように迎えるか、今後、運営委員会や月例会でも協議していければと思います。

歴史的判決の日を、時男さんとともに笑顔で迎えられるよう祈っています。

出典:古屋龍太「裁判結審のご報告」精神国賠研究会会員メーリングリスト2024年6月21日発信

※CALL4への裁判の経過報告掲載が滞り、申し訳ありません。抜けている裁判進捗報告は後日アップさせていただきます。

Report on the 16th oral argument (conclusion).

Despite heavy rain in Tokyo, 62 people attended in the gallery.

The trial itself concluded with the confirmation of the final documents submitted by both the plaintiff and defendant.

The next verdict was announced to be on Tuesday, October 1st at 2pm, and the court adjourned in just three minutes.

After moving through the rain, 67 people attended the trial report meeting by registering at the reception.

We had 24 people connect to Zoom, and some people watched with multiple others, so we believe the total number of people was 99.

We are grateful to the many people who are watching the progress of the trial from afar.

Attorney Hasegawa was unable to attend the report meeting due to urgent business, but Furuya gave the report by reading out the documents that had been compiled.

Below, I will summarize the contents in brackets and include Furuya's impressions.

The documents submitted in this trial were “Plaintiff’s Preparatory Brief 8” and “Defendant’s Preparatory Brief (7).”

Based on the plaintiff's previous cross-examination, the plaintiff's side has organized its arguments to date and put them in writing.

However, the defendant's arguments were very short and only contained factual contentions.

Fact-level assertions

One point of contention is the "type of hospitalization," due to sloppy (or falsified) information being recorded in the medical records.

The plaintiff's side made it clear that "the hospitalization was conducted under the Mental Health Act and was a voluntary hospitalization," and "based on the contents of the medical records and the plaintiff's understanding, he was hospitalized for medical protection until 2003."

The court then stated, "The fact that the form of hospitalization is not clear in the first place stems from flaws in the national system design," and "the reality of forced hospitalization remains unchanged, and the plaintiffs should not be made to suffer the disadvantages that result from this."

On the other hand, the defendant claims that "the plaintiff's form of hospitalization has not been proven."

The reason why the plaintiff was unable to be discharged from the hospital was a topic that was repeatedly raised during the previous cross-examination of the parties.

The plaintiffs argued that "years of inpatient treatment were unnecessary."

The reasons given for this included "I was able to objectively view my symptoms and situation," "I was able to work without any problems," "I was able to be discharged immediately after being transferred to another hospital," and "I am living without any problems since being discharged."

Furthermore, the court pointed out that "both the doctors who treated the plaintiff and the psychiatrist who examined his medical records testified that long-term inpatient treatment was unnecessary."

In response, the defendant argued that "the reason he was unable to be discharged from the hospital was not due to the government's inaction."

The court cited possible reasons for the plaintiff's inability to be discharged from hospital as "possibly due to the plaintiff's illness" and "his family not allowing him to be discharged," and stated that "the plaintiff chose to remain hospitalized, as he thought it would be easier for him to remain hospitalized."

(Regarding this last reason, Tokio also commented at the presentation, "That's a terrible thing to say.")

Regarding violations of the Constitution, such as laws

The plaintiffs argued that "the regulations governing consensual hospitalization and medical protective hospitalization are unconstitutional," "voluntary hospitalization is also unconstitutional because it does not guarantee true voluntariness," and "the psychiatric special provisions are also unconstitutional."

The defendants have not addressed this at all in their filings.

◆ Regarding "illegality" under the State Compensation Act

The plaintiffs argued that "until now, unconstitutionality of legislative inaction has been remedied under the State Compensation Act, and remedies under the State Compensation Act should not be closed in this case either."

In particular, the court stated that "this is a fundamental violation of human rights, namely personal freedom, and its infringement is clear," and that "the failure to amend or repeal the law despite recognition of this is illegal."

He also stated that "fundamental violations of human rights, such as personal freedom," "are the result of the isolation and detention policy that is the basis for this," and that this is a result of national policy.

In particular, the report stated that "medical protective hospitalization gave many private hospitals the authority to involuntarily admit patients," "allowed hospitals to operate with low medical and labor costs," and "the government approved of a policy of isolated confinement."

"If the state is not held responsible in principle no matter what policies it adopts, then it would be like giving private individuals the power by law to restrict the right to pursue happiness, personal liberty, freedom of movement, etc., and the state is not held responsible at all," he stated, stating the injustice of this, and that the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare is "held a duty to act in principle."

The court then ruled that it was illegal for the government to have recognized the human rights violations and yet failed to shift policy toward community-based medical care, provide guidance and supervision to psychiatric hospitals, or provide relief to those forced into long-term hospitalization.

The defendants have not addressed these points at all in their written argument.

Until now, we have argued that for legislative inaction to be considered illegal, it should be limited to limited circumstances, such as when the infringement of rights is clear.

Regarding the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare's duty to act, the court also argues that the duty and authority to act in principle are not unambiguous, and therefore does not recognize any illegality under the State Compensation Act.

◆Participants' opinions

Participants in the trial report session, both in person and via Zoom, responded:

"The defendant country is trying to avoid the issue by reducing it to factual issues."

"Does the defendant country consider that medical protective hospitalization under the current law is lawful and constitutional?"

"Where has the sincere reflection and review that has been given in advisory councils, review committees and the Diet gone?"

"Is the defendant's side not shaken by Tokio's statement?"

Various opinions were expressed.

Summary

The first instance ruling is scheduled to be handed down at 2 p.m. on Tuesday, October 1st.

I have the impression that the time it takes to reach a verdict is unusually long.

What that means is unclear at this point.

Since it is a trial, there are only two options: win or lose, but there can be a fairly wide range of outcomes between the two.

We are seeking a "victory judgment" that recognizes the illegality of the plaintiff's claims under the State Compensation Act.

However, even if a "loss judgment" does not acknowledge illegality under the State Compensation Act, unconstitutionality under the Constitution may still be acknowledged.

It is also possible that the court will not make a judgment on whether a crime is unconstitutional, or that it will decide that medical protective hospitalization is constitutional.

What the defendant country is aiming for is a judgment that dismisses the plaintiff's claim without going into the issue, on the grounds that the plaintiff has not presented any factual evidence.

The wording of the ruling will determine the extent to which it will affect future mental health care policies.

We at the National Institute for Mental Health Compensation have renewed our resolve to work hard and prepare for the verdict on October 1st.

We hope to continue to discuss how we will approach the day of the verdict at future management committee and monthly meetings.

I hope that on the day of this historic verdict, we will be able to greet each other with a smile, along with Tokio.

Source: Ryuta Furuya, "Report on the conclusion of the trial," sent to the Mental Compensation Research Association member mailing list on June 21, 2024

*We apologize for the delay in posting the trial progress report to CALL4. We will post the missing trial progress report at a later date.

第10回・11回・12回口頭弁論:2023年2月21日・5月15日・7月25日

10th, 11th, 12th oral argument: February 21, May 15, July 25, 2023

2024/2/8 16:53

◆第10回・第11回・第12回口頭弁論 2023年2月21日・5月15日・7月25日

第9回裁判期日(昨年11月29日)以降の報告が滞りましたが、2023年に入ってからの第10回~第12回の伊藤裁判の動向をまとめておきます。

第10回(2月21日)、第11回(5月15日)、第12回(7月25日)の裁判では、原告側から様々な証拠書類を提出しています。具体的には、会員各位から寄せられた130名分の証言を集約整理した報告書、専門家の意見書(精神科医6名、福祉関係者3名、憲法学者1名)、韓国の裁判例、国連拷問禁止委員会からの勧告、大阪精神保健福祉審議会(1999年)、精神神経学会等の意見書、原告伊藤さん本人の陳述書等です。

これらを要約する形で提出された原告準備書面6の内容から一部抽出して、原告側の主張を記します。

1 医療保護入院制度は隔離収容目的であり違憲であることについての意見等

・日本の精神障害者の入院は歴史的経緯から社会防衛の機能が重視されてきた

・入退院の医療提供は、病状とは無関係の事情により決定がなされている

・入院の長期化は施設症ないしは退院意欲を喪失させるため、避けなければならない

・精神科病院が適正な医療を提供する場となっていない

・家族を同意者(保護者)とする仕組みが隔離収容を増長させている

2 医療保護入院制度が人権制約の「手段」としても許容されるものではないことについての意見等

・より制約が少ない他の手段をとりえないこと等が規定されていない(韓国の憲法裁判所、日本精神神経学会、国連等でも指摘されている)

・支援を尽くしてもなお本人が入院の是非を判断できないことが規定されていない

・要件が曖昧である

・司法審査が欠如している(指定医の利益相反性など)

・2007年の国連拷問禁止委員会による審査では、「私立病院における民間の精神保健指定医が、精神障害者に対する拘束指示を出すに当たっての役割を担っていること」に懸念を表明しているが、この「拘束指示」の原文は「detention orders」であり、抑留等人身を制約する強制入院をさしている

・入院期間を制限すべき

・精神医療審査会による審査等は機能していない(中立性・独立性に疑義、書面審査は機能していない実態、そもそも退院請求等に至らない実態、審査が適正に行われていない)

・家族の同意は患者の人権擁護として不十分

3 精神科特例の違憲性についての意見等

・精神科においては一般医療以上に医療従事者が必要である

・精神科特例が患者の治療に悪影響を及ぼしている

4 地域医療中心の政策への転換義務違反についての意見等

・クラーク勧告やルコントレポートで「社会復帰施設整備義務」があることが明記されるなど、国には社会復帰施設整備をしなければならないことは明らかであったにもかかわらず、国は、財源の分配、住居、作業所や生活支援の整備などを怠った

・入院医療を民間病院に委ねてきたという先行行為がある以上、民間病院に地域医療でのインセンティブを付与するなど、条理上、国は「地域医療充実義務」を果たす必要があるにもかかわらず、地域医療の促進を怠った

・国が主張する施策については社会復帰に効果的ではなかった

5 精神科病院に対する指導監督義務違反についての意見等

・国は、経営を重視せざるを得ない民間精神科病院を乱立させ、強制入院権限を与え、少ない医療従事者でよしとする政策を実施した(先行行為)のであるから、入院が長期化せず、適正な医療が提供される指導監督する義務があるのに、実質的に機能していない監査しか行っておらず義務を怠った

6 入院治療の必要のない人に対する救済義務違反

・上記同様、国の先行行為によって、入院治療の必要のない人が入院を強いられることとなったという実態があるにも関わらず、国はそれらを救済するための措置を講じてこなかった

・国が主張するような退院促進支援事業は、不要な入院を強いられた人を救済するためのものとして機能していない

7 任意入院の違憲性

・任意入院は、任意性が担保されておらず、強制入院との区別も不適切であり、強制入院と同様の処遇を受けるものものあり、さらに退院制限の仕組みによって強制入院と類似の圧迫感を患者に与えており、実質的には強制入院として用いられている実態がある

8 因果関係

・原告のような社会的入院患者は日本では広く見られており、それらは同意入院・医療保護入院制度や国の政策に起因している

裁判および報告会には、この間55名~85名の傍聴参加者を得ています。今後は法廷での証人尋問を裁判所に求める予定ですが、早ければ2024年春に結審を迎える段階に至っています。ここまで相当な時間を要する作業に取り組んでいただいた弁護団の方々に感謝致します。また、毎回裁判報告会に同席いただき解説をしてくれている長谷川弁護団長に改めてお礼申し上げます。

引用元

古屋龍太「裁判期日(第10回~12回)の報告」精神国賠通信,No.30;1-2,2023年8月

◆10th, 11th, 12th oral argument February 21, May 15, July 25, 2023

There has been a delay in reporting after the 9th trial date (November 29th last year), but we will summarize the trends of the 10th to 12th Ito trials since the beginning of 2023.

In the 10th (February 21st), 11th (May 15th), and 12th (July 25th) trials, the plaintiffs submitted various documentary evidence. Specifically, it includes a report summarizing 130 testimonies submitted by members, written opinions from experts (6 psychiatrists, 3 welfare workers, and 1 constitutional scholar), and a Korean court case. Examples include recommendations from the United Nations Committee against Torture, opinions from the Osaka Mental Health and Welfare Council (1999), the Society of Psychiatry and Neurology, and statements from the plaintiff, Ms. Ito.

We will write down the plaintiff's claims by extracting some of the contents of Plaintiff's Preparatory Document 6, which was submitted in a summary form.

1. Opinions regarding the medical protection hospitalization system being unconstitutional as it is intended for isolation and detention.

・For historical reasons, emphasis has been placed on the function of social defense when it comes to hospitalization of mentally ill people in Japan.

・Decisions regarding the provision of medical care for admission and discharge are made based on circumstances unrelated to the patient's medical condition.

・Prolonged hospitalization must be avoided as it can lead to facility syndrome or loss of desire to leave the hospital.

・Psychiatric hospitals do not provide appropriate medical care

・The system that requires family members to be consenting persons (guardians) is increasing isolation and detention.

2 Opinions regarding the fact that the medical protection hospitalization system is not acceptable as a “means” for restricting human rights.

・It is not stipulated that other less restrictive measures cannot be taken (this has been pointed out by the Korean Constitutional Court, the Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology, the United Nations, etc.)

・It is not stipulated that even after all support is given, the patient still cannot decide whether or not to be hospitalized.

・Requirements are vague

・Lack of judicial review (conflict of interest of designated doctor, etc.)

・A review by the United Nations Committee against Torture in 2007 expressed concern that ``private mental health doctors at private hospitals play a role in issuing restraint orders for mentally ill people.'' The original text of this "detention order" is "detention orders," which refers to forced hospitalization that restricts the person, such as internment.

・Hospitalization period should be limited

・Examinations by the Psychiatric Review Board are not functioning (questions about neutrality/independence, actual situation where written examination is not functioning, actual situation where request for discharge etc. is not reached in the first place, examination is not conducted properly)

・Family consent is not sufficient to protect patient's human rights

3 Opinions regarding the unconstitutionality of special provisions for psychiatry

・Psychiatry requires more medical personnel than general medicine.

・Psychiatric special cases have a negative impact on patient treatment

4 Opinions regarding the violation of the obligation to shift to a policy centered on community medical care, etc.

・Although it was clear that the government had to develop social rehabilitation facilities, as the Clark Recommendation and the Leconte Report clearly stated that there was an obligation to develop social rehabilitation facilities, the government did not have enough financial resources to do so. Neglected the distribution of housing, workspaces, and livelihood support, etc.

・As long as there is a prior act of entrusting inpatient medical care to private hospitals, the government is theoretically required to fulfill its ``obligation to enhance local medical care'' by giving incentives to private hospitals in local medical care. , failed to promote local medical care.

・The measures advocated by the government were not effective for reintegration into society.

5 Opinions, etc. regarding violations of the obligation to provide guidance and supervision to psychiatric hospitals

・The government has created a glut of private psychiatric hospitals that have no choice but to prioritize management, has given them the power to compulsorily admit patients, and has implemented policies that allow for fewer medical personnel (precedent actions), leading to longer hospitalizations. Although the company has a duty to provide guidance and supervision to ensure that appropriate medical care is provided, the company failed to fulfill its duty by conducting audits that were not actually functioning.

6 Violation of duty to provide relief to persons who do not require hospital treatment

・Similar to the above, despite the fact that people who did not need hospital treatment were forced to be hospitalized due to the government's prior actions, the government has not taken any measures to relieve them.

・The discharge promotion support project advocated by the government does not function as a relief for people who are forced into unnecessary hospitalizations.

7. Unconstitutionality of voluntary hospitalization

・Voluntary hospitalization is not guaranteed to be voluntary, and it is inappropriate to distinguish it from compulsory hospitalization. Some cases are treated in the same way as compulsory hospitalization, and furthermore, due to the mechanism of discharge restrictions, it can cause a feeling of pressure similar to compulsory hospitalization. is given to patients, and in reality it is being used as forced hospitalization.

8 Causation

・Social inpatients like the plaintiff are common in Japan, and they are caused by the consent hospitalization/medical protection hospitalization system and national policies.

During this time, 55 to 85 people attended the trial and debriefing session. We plan to request the court to interrogate witnesses in court, but we are at the stage where the case could be concluded in the spring of 2024 at the earliest. I would like to express my gratitude to the attorneys who have worked on this task, which has taken a considerable amount of time. I would also like to once again thank Mr. Hasegawa, Attorney General, for attending each trial report session and providing commentary.

Quote source

Ryuta Furuya “Report on trial dates (10th to 12th)” Shinkokubai Tsushin, No. 30; 1-2, August 2023

第9回口頭弁論:2022年11月29日

9th Oral Argument: November 29, 2022

2024/2/8 16:48

◆第9回口頭弁論 2022年11月29日

精神国賠裁判の直近の様子をお伝えするとともに、今後の展開について私見を述べたいと思います。

まず、第9回裁判期日(2022年11月29日)に多数の傍聴をいただき、ありがとうございました。これまでで最多の73名の方に傍聴席を埋めていただき、その後の裁判報告会にも78名(会場65名+Zoom接続13名)の方にご参加いただきました。中には精神保健福祉士を目指している学部生もおり、真剣に裁判の争点や当事者・家族の発言に耳を傾けていました。

今回の裁判では、被告国側から準備書面(5)が提出されました。これは、これまでに原告側が提出した準備書面3・4・5に対する反論書面になっています。報告会で長谷川弁護士から解説された概要を、かいつまんでご報告します(以下、「 」内は被告国側の主張の要約です)。

1.医療保護入院に関して

(1)同意入院・医療保護入院の目的

被告国側は、「精神障害においては、他の疾病と異なり、本人に病気であることの認識がないなどのため、入院の必要性について本人が適切な判断をすることができず、自己の利益を守ることができない場合があることを考慮し、このような者について、自傷他害のおそれがあるとまではいえないが、医療及び保護のために入院の必要があると認められる場合に適正な医療を提供し、もって、本人の利益を図ることを目的としている」ものであり、原告側が述べるような「隔離収容目的」ではないとしています。

(2)入院要件が曖昧で解釈指針もないこと

原告側が憲法違反であると主張していることに対して「行政手続きにおいて憲法31条は直接適用されない。制限を受ける権利利益の内容、性質、制限の程度、公益の内容、程度、緊急性等を総合的に衡量して決定される」とし、「患者本人の利益を図るという目的は正当であり、人権を過度に制約することのないよう、医師又は指定医が入院必要性を認めたうえで、保護義務者の同意がある場合に限って入院を認めている」「退院の要件、入院中の処遇の基準等の手続き保障の内容が定められており、加えて、精神保健福祉法では医療審査会が設置されており、憲法31条の法意に反しない」と反論しています。

また、国連人権規約(B規約)に反するとの原告の主張に対しては「入院届に対する精神医療審査会の審査でB規約9条4項は満たされている」「自由権規約委員会の一般的意見は、条約解釈を法的に拘束する効力はない」と反論しています。

(3)治療アクセス保証のため

「精神科病院の入院医療は、『自らが病気であるという自覚を持てないときもある精神疾患では、入院して治療する必要がある場合に、本人に適切な入院医療を受けられるようにすることは、治療へのアクセスを保証する観点から重要である』ということは、医師、自治体、学識者のみならず、当事者を含めて共通の認識であり(平成24年のあり方検討会の「入院制度に関する議論の整理」)、そのことは今でも変わらない」としています。

「医療保護入院を即時に廃止するような方向性が共通認識として示されたことはない」し、「国が行ってきた法令改正は、医療の進歩等を踏まえつつ、最善の制度を提供できるよう検討及び改正を重ねており、かつ、権利擁護や地域移行の観点から必要な措置を採ったもの」であるとして、「原告が退院できなかったことをもって直ちに、医療保護入院制度が憲法上の権利侵害が明白であるとはいえない」と結論付けています。

(4)医療観察法との比較

「法律の目的が大きく異なるなど、両法律を単純に比較することはできない」と退けています。

2.任意入院制度に関して

任意入院制度が強制性を含んでいるとの原告の主張に対して、「任意入院は、非強制という状態での入院を促進することに中心的意義がある」。「入院に際しては、患者自ら入院する旨を記載した書面が求められている。退院等請求もできる。退院の申し出があれば原則として退院させなければならない」制度となっているとして、「一般的に、運用として、入院が医師の一方的な判断で行われたり、患者の同意の任意性が確保されないものであるなどとは言えない。任意入院の規定が憲法上の権利侵害が明白であるとはいえない」と反論しています。

3.精神科特例に関して

精神科特例により、他診療科に比して差別的な人員配置となっているとの原告の主張に対して、「精神科特例は、医師及び看護師等の配置基準を緩和したものであり、他のスタッフとは何ら規定がされていない」として「原告の主張も医師及び看護師等の配置基準との関係については主張が具体的ではない」と反論しています。

さらに「全ての医療において、慢性的な治療を要する疾病は存在する。精神科医療においては、精神疾患の多くが慢性である、あるいは病状の急変が少ないという特質を踏まえつつ、あらゆるニーズに対応した精神科医療を想定する必要がある。また、精神科特例は、あくまで暫定的な運用として特例を示したものであることに加え、精神科特例そのものが入退院の時期を定めるものではない」として、「厚生大臣が原告との関係において精神科特例を廃止すべき義務は負わない」と結論付けています。

4.地域医療政策転換義務に関して

原告側の訴えに対して、被告国側は「前提として、法令の規定やその趣旨目的に照らし、作為義務の内容が明確ではない」としたうえで、「昭和40年に中間答申等の指摘や精神医学の進歩による医療体制の変化に基づいて精神衛生法の改正を行なった」「昭和41年に『保健所における精神衛生業務運営要領』、昭和44年に『精神衛生センター運営要領』、昭和50年に『精神障害回復者社会復帰施設』及び『デイ・ケア施設』の運営要領、昭和55年に『精神衛生社会生活適応施設』の運営要領等を示しており、以後も適切に施策を講じている」と述べ、「厚生大臣及び厚労大臣に違法な不作為がないことは明らかである」と結論付けています。

5.精神病院に対する指導監督義務違反

原告側の主張に対して、被告国側は、「すでに被告準備書面(3)で述べたとおりである」として、それ以上の言及はありませんでした。

6.社会的入院者に対する救済義務違反

社会的入院者に対する救済義務が被告国にはあったとする原告の主張に対して、「前提として、法令の規定やその趣旨目的に照らし、作為義務の内容が明確ではない」とし、「これまでも『積極的な退院支援』や『積極的調査介入義務』は国の施策として行ってきた」と反論しています。

7.今回の裁判の評価

上記のように、今回の被告国側の反論は、これまで被告国側が述べてきたことを再度繰り返す内容にとどまりました。これまで「精神国賠通信」紙上でも掲載してきた、被告国側の主張を読んでいただければわかるように、特に目新しい記述もなく、分量もA4判で20ページに満たない薄いものでした。

特に立法府(国会)の不作為責任について追及した原告側の主張に対しては、ほぼ無回答で、行政府(厚生労働大臣)の責任についても「主張が明確ではない」「作為義務は負わない」「違法な不作為はない」と繰り返すのみでした。前回裁判で「反論に時間を要する」として3か月後の開廷を求めたのは、果たして何だったのでしょう。いたずらにただ待たされた感が残ります。

おそらく(これは私見の憶測ですが)、この裁判と同時並行で準備され、国会に上程された「精神保健福祉法一部改正案」を含む「障害者総合支援法等一括改正案」(いわゆる束ね法案)の審議への影響が及ばぬようにということで、省内調整等が為されていたのではないでしょうか。いずれにせよ、新しい反論主張も無いまま「以上!」と締めにかかった感があります。

ちなみに、この法案については、精神国賠研としても見過ごすことができないとの月例会での議論もあり、専門部会で協議して見解をまとめました。12月5日付で参議院の厚生委員の議員たち16名にファックスで送っています。

8.今後の裁判の展開

第9回期日の最後に、原告弁護団からは証言資料を提出することを求め、裁判長に許可されました。これを受けて、次回の第10回期日では、原告弁護団より「証言陳述書」が証拠資料として提出される運びとなりました。この間、会員の皆さんにご協力いただき寄せていただいた、当事者・家族・専門職の「証言陳述書」を通して、日本の精神医療の状況は、この裁判の原告の伊藤時男さんだけでなく、等しく各地で体験されていることを法廷に示していくこととなります。

また、合わせて原告弁護団は、この裁判で問われている隔離収容政策の歴史的経緯や現行の入院制度・精神医療審査会等の問題について、精神科医等の識者に意見を求めることを決め、専門部会でその人選を協議してきています。

裁判はいよいよ大詰めを迎えようとしています。一人ひとりができることは限られていますが、可能な方は第10回期日の法廷に来て、傍聴席から見守っていただけたらと思います。

引用元

古屋龍太「第9回裁判期日と今後の展開」精神国賠通信,No.28;3-5,2023年1月発行

◆9th Oral Argument November 29, 2022

I would like to share with you the latest developments in the National Compensation Tribunal, as well as offer my personal opinion on future developments.

First of all, I would like to thank the large number of people who attended the hearing on the 9th trial date (November 29, 2022). A total of 73 people filled the audience seats, the largest number ever, and 78 people (65 people at the venue + 13 people connected via Zoom) participated in the subsequent trial report session. Some of the undergraduate students were aiming to become mental health workers, and they listened intently to the issues at issue in the trial and the statements of the parties and their families.

In this case, the defendant country submitted a preliminary document (5). This is a written rebuttal to Preparatory Documents 3, 4, and 5 that the plaintiff has submitted so far. I would like to briefly report on the summary explained by Attorney Hasegawa at the briefing session (below, the text in parentheses is a summary of the defendant country's argument).

1. Regarding medical protection hospitalization

(1) Purpose of consent hospitalization/medical protection hospitalization

The defendant's side stated, ``Unlike other illnesses, with mental disorders, the person is not aware that he or she is sick, so the person is unable to make an appropriate judgment regarding the need for hospitalization, and Taking into consideration that there may be cases in which it is not possible to protect the interests of such persons, cases where it is deemed necessary for such persons to be hospitalized for medical care and protection, although it cannot be said that there is a risk of harm to themselves or others. The purpose of the facility is to provide appropriate medical care to the patient and thereby benefit the patient," and is not intended to be "isolated and detained," as stated by the plaintiffs.

(2) Hospitalization requirements are vague and there are no interpretation guidelines.

In response to the plaintiff's claim that there is a violation of the Constitution, ``Article 31 of the Constitution is not directly applied in administrative procedures. ``The purpose of protecting the patient's interests is legitimate, and the patient's human rights are not unduly restricted, so the doctor or designated doctor recognizes the need for hospitalization.'' ``Hospitalization is permitted only with the consent of the guardian.'' ``Requirements for discharge, standards for treatment during hospitalization, etc. are stipulated, and in addition, the Mental Health and Welfare Act A medical review board has been established, and this does not violate the legal intent of Article 31 of the Constitution.''

In addition, in response to the plaintiff's claim that it violates the United Nations Human Rights Covenant (B Covenant), ``The Psychiatric Review Committee's review of the hospitalization notification confirmed that Article 9, Paragraph 4 of the B Covenant was satisfied'' and ``The International Covenant on Human Rights Committee ``General opinions have no legal binding effect on treaty interpretation.''

(3) To guarantee access to treatment

``Inpatient medical care at psychiatric hospitals is aimed at ensuring that patients receive appropriate inpatient medical care when they need to be hospitalized for mental illnesses in which they may not even be aware that they are sick.'' This is important from the perspective of guaranteeing access to treatment.'' This is a common recognition not only by doctors, local governments, and academics, but also by those who are involved. ``Organizing debates regarding the system''), and that remains the case.''

``There has never been a consensus on the direction of immediately abolishing medically protected hospitalization,'' and ``the legal revisions that the government has carried out will provide the best possible system, taking into account advances in medical care.'' ``As a result of the plaintiff's inability to be discharged, the medical protection hospitalization system was immediately revoked under the Constitution.'' It concludes that there is no obvious violation of rights.

(4) Comparison with medical observation method

``The two laws cannot be compared simply because their objectives are very different.''

2. Regarding the voluntary hospitalization system

In response to the plaintiff's argument that the voluntary hospitalization system includes compulsion, ``the central significance of voluntary hospitalization is to promote hospitalization in a non-compulsory manner.'' ``When being hospitalized, patients are required to submit a document stating that they will be hospitalized.They can also request discharge, etc.If a request for discharge is made, in principle, the patient must be discharged.'' Furthermore, it cannot be said that hospitalization is carried out based on the doctor's unilateral decision or that the patient's consent is not guaranteed.The provision of voluntary hospitalization is a clear violation of constitutional rights. "I can't say that," he argues.

3. Regarding special cases of psychiatry

In response to the plaintiff's claim that the special provisions for psychiatry result in discriminatory staffing compared to other medical departments, the plaintiff said, ``The special provisions for psychiatry are a relaxation of standards for the placement of doctors, nurses, etc. ``There are no regulations regarding the standards for the placement of doctors, nurses, etc.'' and ``the plaintiff's claims are not specific regarding the relationship with the standards for the placement of doctors, nurses, etc.''

Furthermore, ``In all medical fields, there are diseases that require chronic treatment.In psychiatric medical care, we strive to respond to all needs, taking into account the characteristics of most mental illnesses that are chronic or that their condition rarely changes suddenly.'' Psychiatric medical care needs to be considered.In addition, the psychiatric special provisions are only a provisional provision, and the psychiatric special provisions themselves do not determine the timing of admission or discharge." The court concluded that ``the Minister of Health and Welfare has no obligation to abolish the psychiatric special provisions in relation to the plaintiff.''

4. Regarding the obligation to change local medical policy

In response to the plaintiff's complaint, the defendant country stated, ``Based on the premise, the content of the obligation to act is not clear in light of the provisions of the law and its purpose and purpose,'' and added, ``The content of the obligation to act is not clear in light of the provisions of the law and its purpose and purpose.'' The Mental Hygiene Act was revised based on the changes in the medical system due to advances in psychiatry and psychiatry.''In 1966, the ``Guidelines for the Management of Mental Hygiene Services at Public Health Centers'' was published, and in 1966, the ``Guidelines for the Management of Mental Health Centers'' were published. In 1950, operating guidelines for ``social reintegration facilities for persons recovering from mental disorders'' and ``day care facilities'' were established, and in 1980, operating guidelines for ``mental health and social life adaptation facilities'' were established, and appropriate measures have been continued since then. ``It is clear that the Minister of Health, Labor and Welfare and the Minister of Health, Labor and Welfare have not taken any illegal action.''

5. Violation of duty to provide guidance and supervision to a mental hospital

In response to the plaintiff's claim, the defendant state did not make any further comment, stating that ``this is already stated in the defendant's preliminary document (3).''

6. Violation of duty to provide relief to social inpatients

In response to the plaintiff's argument that the defendant state had an obligation to provide relief to socially hospitalized patients, it stated, ``As a premise, the content of the obligation to act is not clear in light of the provisions of the law and its purpose and purpose.'' ``Active discharge support'' and ``obligation to proactively investigate and intervene'' have been implemented as national policies.''

7. Evaluation of this trial

As mentioned above, the defendant's rebuttal this time was merely a reiteration of what the defendant had previously stated. As you can see by reading the defendant country's argument, which has been published in the Shinkokuba Tsushin newspaper, there is nothing particularly new about it, and the content is short, less than 20 A4 pages.

In particular, there was almost no response to the plaintiff's claims regarding the liability of the legislative branch (National Diet) for inaction, and regarding the responsibility of the executive branch (Minister of Health, Labor and Welfare), ``the claims are not clear'' and ``there is no obligation to act.'' ``There was no illegal omission,'' he simply repeated. What was the point in the previous trial when they requested that the trial be held in three months, saying that ``it would take time to make a counterargument''? I still feel like I was made to wait for a prank.

Perhaps (this is just speculation in my opinion) the ``Blank Amendment Bill for the Comprehensive Support Act for Persons with Disabilities,'' which includes the ``Mental Health and Welfare Act Partial Amendment Bill'' (so-called I believe that adjustments were made within the ministry to ensure that the deliberations on the Bundled Bill were not affected. In any case, I feel like the discussion ended with "That's it!" without any new counterarguments.

By the way, there was a discussion at the monthly meeting that the Psychiatric and National Health Insurance Research Institute cannot overlook this bill, so we discussed it in the expert committee and compiled our views. It was sent by fax on December 5th to 16 members of the Health and Welfare Committee of the House of Councilors.

8. Future developments in the trial

At the end of the 9th session, the plaintiff's legal team requested the submission of testimonial materials and was granted permission by the presiding judge. In response to this, the plaintiff's legal team will submit a "testimony statement" as evidence at the next 10th hearing. During this time, through the "testimony statements" of the parties, their families, and professionals, which we received with the cooperation of our members, we were able to understand the state of mental health care in Japan, not just for the plaintiff in this case, Tokio Ito, but equally. We will be able to show the court what is being experienced in each region.

In addition, the plaintiff's legal team will seek opinions from experts such as psychiatrists regarding the historical background of the segregation and detention policy, the current hospitalization system, and the Mental Health Care Review Board, which are being questioned in this trial. A special committee has been discussing the selection of the person.

The trial is about to reach its final stage. There is a limit to what each individual can do, but if you are able, I would like you to come to the courtroom for the 10th session and watch from the audience seats.

Quote source

Ryuta Furuya, “9th Trial Date and Future Developments,” Shinkokubai Tsushin, No. 28; 3-5, published January 2023

第7回・第8回口頭弁論:2022年5月16日・8月22日

7th・8th Oral Arguments: 5/16,8/22, 2022

2024/2/8 16:45

◆第7回・第8回口頭弁論 2022年5月16日・2022年8月22日

伊藤時男さんを原告とする精神国賠裁判は、これまでの8回の裁判が行われています。今回は、第9回の裁判(11月19日13時半開廷)に向けて、これまでの概要を共有しておければと思います。

1.第7回期日(2022年5月16日)

原告側弁護団より「原告準備書面3及び4」が提出されました。原告準備書面3では、入院治療の必要性のない強制入院は憲法上許容されないこと、原告には入院治療の必要性がなかったこと、国の不作為により原告が退院できなかったこと、原告の権利侵害に対しても国はそれを解消する義務を負うべきことが述べられています。また、原告準備書面4では、同意入院及び医療保護入院の違憲性について、人身の自由に対する制約という観点から主張が追加されています。その原告側の主張内容を、当日の裁判報告会資料からまとめておきます。

(1)入院治療の必要性のない強制入院

前回(第6回)の裁判で、被告国側は原告の入院形態について、「カルテに定期病状報告書の記載がないことから、医療保護入院ではない」と反論をしました。原告の伊藤さんの入院形態については、双葉病院入院当時(1973年)が精神衛生法時代であり、まだ制度上「任意入院」は存在しないことから「同意入院」(現在の医療保護入院)であったことは明らかです。ただカルテが杜撰なため、いつまでが同意入院であったか記されていませんが、記載されている内容や任意入院の同意書が添付されていないことから、カルテの転帰日に記された2003年(平成15年)4月としか考えられません。入院形態の記載はなくとも、実態としては入院を強制され続けてきたことは明らかで、医療保護入院がいつまでであったかの終期が確定できないことを理由として、国の責任が否定されるべきではありません。

伊藤さんに長期にわたる入院治療の必要性がなかったことは、入院時の様子や退院後の状態から明らかです。国の不作為により伊藤さんが退院できずにさまざまな権利侵害が生じたのは、日本の精神医療に関する法や政策の問題であることを、多くの精神科医師らが証言しています。この状態が生じたのは、これまでの精神保健法~精神保健福祉法が、医師に極めて広範な裁量権を与える医療保護入院制度や、患者本人の任意性をなんら担保せず事実上の強制入院を認める任意入院制度を、長年にわたって放置してきたためです。また、少ないスタッフ配置を当たり前にして精神医療の質を著しく低下させ、安上がりの低医療費・低人件費の原因ともなった「精神科特例」が放置されてきたからにほかなりません。さらに、地域医療政策への転換や精神病院への指導監督を国が怠ったからであり、社会的入院者に対する積極的な調査介入救済をせずに放置してきたからにほかなりません。国が作出した法や政策によって、伊藤さんの不要な長期入院という権利侵害が生じているのであり、国がその権利侵害を解消する義務を負うのは当然、と原告は主張しました。

(2)国による積極的救済の必要性

国が、社会的入院者に対して積極的に救済しなければならない根拠の一つとして、被収容者の心理性の問題があげられます。長期にわたる閉鎖的な施設生活の継続により、人が無意欲状態となり無力化されることは、社会学者E・ゴッフマンの『アサイラム』の研究などから明らかにされています。(旧)全国精神障害者家族連合会も、施設症と社会的入院について全国的な調査を行ったうえで、「施設症」を生み出す精神科医療の構造は全国的に普遍的に存在すること、その背景には少ないスタッフ基準や低い開放病床率、長い平均在院日数、社会復帰活動への取り組みの乏しさ、そして地域の社会資源の乏しさ等が関与することを明らかにしています(ぜんかれんモノグラフNo.15「長期入院者の施設ケアのあり方に関する調査研究」)。これらの背景を解消できるのは国しかなく、国は原告に対して権利侵害を解消すべき義務がある、と原告側は主張しました。

(3)医療保護入院の違憲性

医療保護入院の違憲性については、これまでも原告弁護団が主張してきたことです。今回は、強制入院が人身の自由の制約そのものであるという観点から追加して主張を行いました。患者の判断能力の欠如を強制入院の要件としていなかった同意入院制度は明らかに違憲であり、のちにこの要件が付け加えられた医療保護入院も、曖昧な入院要件が放置され、未だに手続きも不十分なままであり、憲法31条(適正手続の保障)に違反します。実際に、社会的入院と呼ばれる状態の入院患者は1983年以降、5万人以上も存在し続けるなど、医療保護入院が厳格に運用されていないことは明らかです。また、合憲限定解釈※のような運用もなされておらず、医療保護入院は違憲状態にあるといえます。

※合憲限定解釈:法律を違憲と判断する余地はあるが、裁判所が条文の意味を限定的に解釈することによって合憲と解釈する、違憲判断回避の方法の一つ。

2.第8回期日(2022年8月22日)

前回(第7回)は、原告側から行政府(厚生労働大臣)の不作為を主張しましたが、今回は改めて原告側から立法府(国会)の不作為事実を示す「原告準備書面5」と証拠資料が提出されました。本裁判の被告は国であり、厚生労働省だけでなく、法律を改廃してこなかった国会の不作為責任も問うているのです。

立法府における精神医療政策の不作為事実を列挙するために、1965年~2005年の約0年間にわたる膨大な量の国会議事録を弁護団は精査しました。精神国賠研の専門部会も資料探索には協力していますが、弁護団の地道な探索作業により、成し遂げられた証拠資料の提示でした。国会(衆議院・参議院)における国会議員(与野党)の質問事項と厚生(労働)大臣及び政府委員の答弁や、参考人の意見陳述等を抽出したものです。この作業により、精神科医療をめぐるさまざまな問題が生じていることを、大臣や議員たちは早い段階で認識し議論していたことが明らかとなりました。

国会での主要な論点をピックアップすると、①社会的入院の問題(社会復帰対策を含む)、②精神科特例の問題、③精神医療審査会の問題、④地域精神医療への転換、⑤医療保護入院制度の問題、⑥任意入院制度の問題、⑦ハンセン病同様の隔離収容政策の問題、等が挙げられます。精神科医療をめぐる問題は国会でも繰り返し議論されてきており、国会議員も政府もあまたの課題を認識していたこと、作為義務を負いながら抜本的改革に着手せず先延ばしにしてきたことを示し、立法府の不作為責任を追及しています。

準備書面ではさらに、日本精神科病院協会会長も「いわゆる社会的入院と呼ばれるものは国の無策の産物」であり「国は精神障害者・精神医療関係者・国民に詫びるべき」と批判していることも付け加えています。

ここまで、だいたい裁判は2か月おきの間隔で開かれてきましたが、被告国側は「反論に少々時間を要する」と3か月後の裁判期日設定を求め、第9回期日は11月29日(火)と定められました。

3.第9回期日に向けて

第9回口頭弁論では、被告国側からの反論を示す準備書面が提出されます。原告弁護団が示した証拠資料に対して、どのような反論を行うのか、注目されるところです。

第2回期日以降、ずっと東京地裁で最も大きい法廷(103号法廷:傍聴席100席)が使われてきましたが、コロナ対策の傍聴席定数制限(1/2=50席)が解除されていることから、30名~40名程度の傍聴人では、空席が目立ち、少人数の法廷に変更される可能性ができてました。お時間に都合の付く方は、ぜひ東京地裁までお越しいただければ幸いです。

引用元

古屋龍太「第7回・第8回口頭弁論の概要―行政府・立法府の不作為責任を追及」精神国賠通信,No.26;1-3,2022年10月発行

◆7th and 8th Oral Arguments May 16, 2022, August 22, 2022

Eight trials have been held so far in the mental health compensation trial in which Tokio Ito is the plaintiff. This time, I would like to share an overview of what has happened so far in preparation for the 9th trial (opening at 1:30pm on November 19th).

1. 7th date (May 16, 2022)

Plaintiff's lawyers have submitted "Plaintiff Preparatory Documents 3 and 4." Plaintiff Preparation 3 states that forced hospitalization without the need for inpatient treatment is constitutionally unacceptable, that the plaintiff had no need for inpatient treatment, that the plaintiff was unable to be discharged due to the government's inaction, and that the plaintiff's rights It also states that the state has an obligation to eliminate infringements. In addition, Plaintiff Preparatory Document 4 adds an argument regarding the unconstitutionality of consensual hospitalization and medical protection hospitalization from the perspective of restrictions on personal freedom. We will summarize the content of the plaintiff's arguments from the trial report materials from that day.

(1) Forced hospitalization without the need for inpatient treatment

In the previous (sixth) trial, the defendant country argued that the plaintiff's type of hospitalization was not a medical protection hospitalization because there was no periodic medical report in the patient's medical record. Regarding the type of hospitalization of the plaintiff, Mr. Ito, at the time of his admission to Futaba Hospital (1973), it was the era of the Mental Hygiene Law, and "voluntary hospitalization" did not yet exist in the system, so it was "hospitalization with consent" (currently medical protection hospitalization). It's clear that there was. However, due to the medical records being sloppy, it is not written how long the patient was hospitalized with consent, but since the written contents and the consent form for voluntary hospitalization were not attached, the date of the outcome in the medical record was 2003 (2003). I can only think of April 2003. Even if there is no mention of the type of hospitalization, it is clear that the patient was forced to continue to be hospitalized, and the responsibility of the state should not be denied just because it is not possible to determine the end of the period of medical protection hospitalization. .

It is clear that Mr. Ito did not need long-term hospital treatment from his condition at the time of admission and his condition after discharge. Many psychiatrists have testified that the reason Ms. Ito was not discharged from the hospital and various rights violations occurred due to the government's inaction is a problem with Japan's mental health laws and policies. This situation has arisen because the previous Mental Health Act and Mental Health Welfare Act have introduced a medical protection hospitalization system that gives extremely wide discretionary powers to doctors, and a de facto coercion system that does not guarantee the patient's voluntariness. This is because the voluntary hospitalization system that allows hospitalization has been neglected for many years. Furthermore, this is due to the neglect of the ``psychiatry special provisions,'' which have made it commonplace to have fewer staff members and have significantly lowered the quality of mental health care, leading to low medical costs and low labor costs. Furthermore, this is because the government has neglected to shift to a regional medical policy and provide guidance and supervision to psychiatric hospitals, and has left social inpatients without any active investigation or intervention. The plaintiffs argued that the laws and policies created by the government had caused the violation of Ms. Ito's rights by requiring her to be hospitalized for an unnecessary long period of time, and that it was natural for the government to have an obligation to eliminate the violation of her rights.

(2) The need for active relief by the state

One of the reasons why the state must proactively provide relief to socially hospitalized inmates is the psychological problem of the inmates. Studies such as sociologist E. Goffman's ``Asylum'' have shown that living in a closed facility for a long period of time leaves people in a state of apathy and powerlessness. The (former) National Federation of Families of the Mentally Disabled also conducted a nationwide survey on institutionalism and social hospitalization, and found that the structure of psychiatric medical care that produces "institutionalism" exists universally throughout the country. It has been revealed that the reasons behind this are low staff standards, low open bed rate, long average length of stay in hospital, lack of efforts to reintegrate into society, and lack of local social resources. Karen Monograph No. 15 "Research on the state of facility care for long-term hospitalized patients"). The plaintiffs argued that only the state can resolve these backgrounds, and that the state has an obligation to the plaintiffs to eliminate rights infringements.

(3) Unconstitutionality of medical protection hospitalization

The plaintiff's legal team has long argued that medically protected hospitalization is unconstitutional. This time, I made an additional argument from the perspective that forced hospitalization is itself a restriction on personal freedom. The consent hospitalization system, which did not require a patient's lack of decision-making capacity as a requirement for compulsory hospitalization, is clearly unconstitutional, and the medical protection hospitalization system, to which this requirement was later added, has left ambiguous hospitalization requirements and is still poorly processed. This remains sufficient and violates Article 31 (guarantee of due process) of the Constitution. In fact, since 1983, there have been more than 50,000 hospitalized patients with a condition called social hospitalization, and it is clear that medical protection hospitalization is not strictly implemented. In addition, the limited constitutional interpretation* has not been implemented, and it can be said that medically protected hospitalization is unconstitutional.

*Limited interpretation of constitutionality: Although there is room for a law to be judged unconstitutional, the court interprets it as constitutional by restricting the meaning of the provision, which is one way to avoid a judgment of unconstitutionality.

2. 8th date (August 22, 2022)

Last time (7th session), the plaintiff claimed inaction on the part of the executive branch (Minister of Health, Labor and Welfare), but this time, the plaintiff once again presented "Plaintiff Preparation Document 5" and evidence showing inaction on the part of the legislative branch (National Diet). Materials have been submitted. The defendant in this case is the government, and it is not only holding the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare responsible for its inaction, but also the Diet, which has not amended or repealed the law.