What we can do to protect our information by “building a better system by raising our voices.”

2019.5.14

2019.5.14

Yukiko Miki and a story of information disclosure / personal information protection

“These days, we leave a trail of information behind us everywhere we go,” says Yukiko Miki.

“It’s been a long time since Japan has become a surveillance society. From smartphone to IC card, what you do with them is indelibly associated with your name. We never know how our data is collected or used.”

We went to a non-profit organization, Information Disclosure Clearing House, to interview the director, Yukiko Miki. She told us a story about a lawsuit seeking disclosure of personal information files held by the National Police Agency. The Clearing House was established in 1980 as a citizen’s movement for the Freedom of Information Act. It has continued to work with Japan Civil Liberties Union (JCLU) to create a system to protect citizens’ privacy and data, covering areas such as information disclosure, the management of official documents, and t protection of personal information.

I was not familiar with information-related systems, including the information disclosure system. So I wondered what this lawsuit was for. I found it difficult to imagine what a surveillance society looks like. I felt a vague fear and anxiety about it, but I just didn’t know how my information was used.

Miki explains to me, “For example, think of the activities of administrative agencies of government. They collect information on residents for criminal investigations, and the collected data is accumulated on their system. Also, you never know what information they collect. They may have your data, or have you under secret surveillance and storing results, just because you belong to a particular community. –i.e., you believe in Islam, or you are a member of a non-profit organization with a history. “

Miki’s story helped me understand the history of the fight for the protection of information privacy and the power of the citizens to influence administrative actions by keep demanding the right to privacy is protected, respected, and fulfilled.

The Information Disclosure Litigation—What is wrong with blacked-out information?

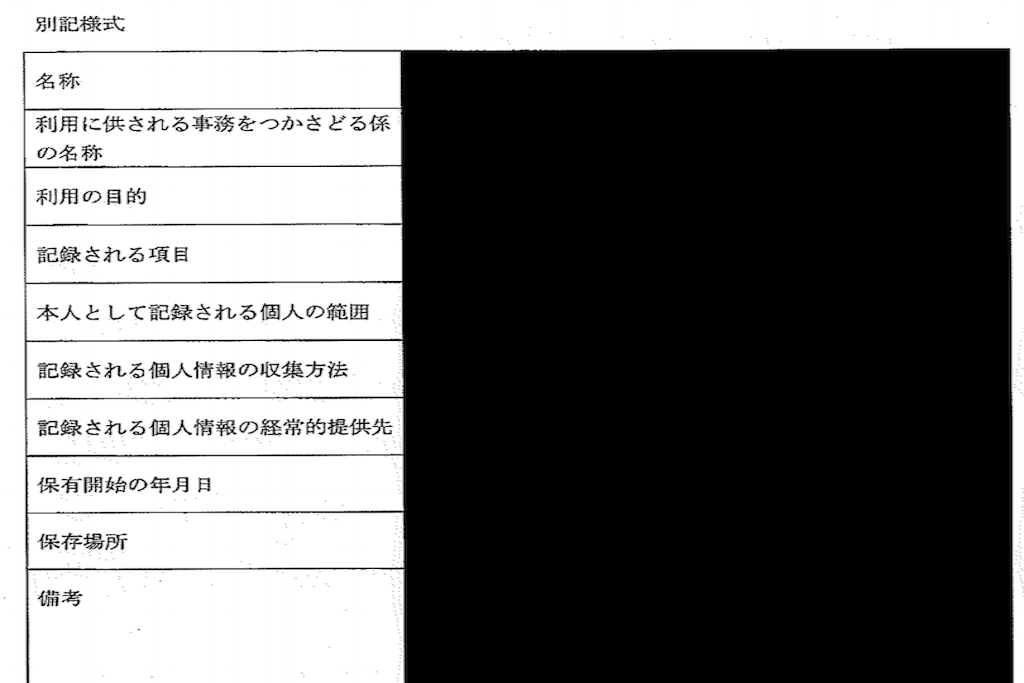

In this case, Miki is asking for disclosure of not the contents, but the titles of personal data files managed by the National Police Agency.

“We want to know how much and what kind of personal information the National Police Agency collects,” says Miki.

“According to the law (Administrative Agency Act on the Protection of Personal Information,) we the citizens have the right to know what kind of information is being gathered,” she explains.

“When I asked for disclosure in 2015, they sent me more than 120 documents that were completely blacked out, not just the titles but also their content.”

So, the government ‘disclosed’ 122 files that were completely blacked out.

Miki pointed to the blacked-out files and laughed, “These days, they don’t use oil-based markers. If you blot out all these pages with a marker pen, you would be intoxicated.”

So, what’s wrong with blacked-out information?

“No one questions the roles of the police. What we are talking about here is how we can make the activities of the public sector, such as crime investigation, more transparent and accountable,” says Miki. “It is unclear what kind of personal information is collected and used, by which organizations, for what duration, and for what purposes. We need the answers to all these questions, and this should be discussed by citizens.”

“These files contain personal information. If they are not disclosed to the public, it means we lose the chance to monitor the data collection activities by public authorities. And it is especially important for the field of criminal justice where may potentially be a breach of human rights because the disclosure of individual records is limited.”

We promote the more appropriate use of information owned by the authorities. Miki explains how the black-out files started litigation.

“Then, in 2018, we requested to disclose specific files, including “personal information files concerning the DNA Profile Information Database” and “personal information files concerning the fingerprint database.” In the end, some parts of the eighteen files were disclosed. This time, they didn’t black out the titles, responsible departments, and the types of information collected.”

Files that are no longer completely blacked out.

“These eighteen files are part of the 122 files mentioned earlier. In other words, if we ask to disclosed many files, they blot out everything, but if we ask for specific files, they leave some parts of the same files as they are. So, we decided to bring a lawsuit to request the disclosure of the 122 files.”

The National Police Agency claims that the blacked-out areas contain information that “could harm the security of the country” and “may interfere with criminal investigations.” With most parts of the 18 files being disclosed, Miki thinks that they blot out information that can be disclosed without any problem, and thus it is arbitrary non-disclosure based on abstract fears.

Currently, Miki is involved in three other lawsuits to claim the disclosure of personal information.

Miki said, “Class action lawsuits involving information disclosure used to be mostly about the right of access to personal data held by government agencies and other public institutions. But in the past few years, we have been exclusively pursuing legal action for the disclosure of information concerning Japanese foreign and security policies, and public safety.” Her office is lined with bookcases, filled with files upon files of documents that she has collected since the 1970s.

“Our underlying idea has been the same. Public documents belong to everyone, and the right to know must be protected. We are trying to enhance social control over the government bureaucracy through studying the policies, activities, and practices of the administration.”

Miki deliberately explained why it is vital for us to know all that.

Civilians should think about how best to use public information. And the same goes for personal data.

If we leave everything to the administrative authorities, why would that be a problem?

Miki argues that we should create a tension between the public and state authorities around the matter of information to make adequate use of public information, and the same logic can be applied to the protection of personal data. In both cases, we can exercise democratic control over state authorities by systematically controlling information owned by the administration.

“When the Act on the Protection of Personal Information (APPI) in which media regulation was identified as a key issue, the Act on the Protection of Personal Information Held by Administrative Organs was also completely revised. The laws were enforced in 2005 when there was an increased public awareness of data protection. However, at the same time, a new system was born, which worked in the opposite direction to these changes, allowing personal information to be disclosed to the public. This happened when the Basic Resident Registration Act was revised in 2006.”

“It first started as a citizen’s initiative.”

Up until 2005, anyone could request to see the Basic Resident Registration Ledger at any city, town, or village. The register included address, full name, the date of birth, and sex of all residents.

“Confidential data of residents were freely accessible back then, and many businesses used this information to send direct marketing. So we called for volunteers to help us look into this matter at over a hundred local governments. It turned out there were many problems.”

The Basic Resident Registration Ledger was open to the public, and sales and marketing companies, as well as fraudsters in phone scams targeting the elderly, have been using it to collect personal information. There was an indecent assault case targeting children from single-parent households in Nagoya. When the suspect was arrested, the police found a huge amount of printed pages from the Ledger.

“Previous to this incident, local governments had long been aware of the security concerns of the Basic Resident Registration Ledger and have requested a change in the law. So they started campaigning for an amendment to the law as soon as the details of the crime were made public. As a result, the regulations for viewing the Ledger were changed across the country. Many local assemblies adopted a written opinion on the proposed amendment to the law, and a few of them enacted an ordinance to limit the access to the Ledger. In response to these changes in society, the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, which had been opposed to such amendments, began to work towards changing the law.”

Miki explained, “This case exemplifies how citizens can start a discussion, make their voices heard, and change the way society is organized.” She pointed out that by discussing and acting, we as citizens can be a catalyst for developing and implementing security systems for protecting personal information.

Why she continues to fight for society.

Miki has been involved in civil movements around information privacy since the mid-1990s. In addition to working for the Clearinghouse, she has served as a member of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government’s Information Disclosure Ordinance Revision committee, Information Disclosure, and Personal Information Protection Council of Kunitachi City, and Nagano Prefecture’s Information Disclosure and Personal Information Protection Review Board. She has also been working at many levels in the development of various systems for information disclosure and the protection of personal information.

Her first involvement in social activities was more than twenty years ago when she requested the disclosure of her personal information using an information disclosure system.

“It was when I went to university. At that time, the National Center Test scores were not disclosed. Even now, you have to mark your answers to know how much you scored. I thought it strange that they wouldn’t let you know your score, because it was a piece of important information upon which you decide which university to apply to.”

“The standardized test operator National Center for University Entrance Examinations is a national institution, but at that time, they didn’t have any information disclosure system for those who took the test. I went to a public university, and I heard that you could request the disclosure of your test scores held by public universities in accordance with local ordinances. So, as soon as I started school in April, I made a disclosure request.”

At first, she “only wanted to ask whether the system should deny our right to access one’s data.” Miki said, “I realized that my request was personal yet public because if my request is accepted, it means everyone who takes the test can have access to their scores. And thus, my action could inspire a change in society.”

Unfortunately, her request was denied that time, and her appeal was dismissed. When she spoke to a lawyer, with whom she had worked at the Japan Civil Liberties Union (JCLU) about the case, she was advised to file a public interest case in court. Soon after that, a delegation of lawyers of JCLU volunteered to take the case on a pro bono basis. With their support, Miki decided to bring the case to the court while she was at university. (Even now, JCLU is working with the Clearing House and providing full support for her four cases of information disclosure lawsuit.)

The lawsuit was rejected by the district court and the high court and then by the Supreme Court. However, the Information Disclosure Act came into force during that time, and the way of disclosure of entrance examination information changed.

In 2001, shortly after the National Center for University Entrance Examinations stated to send official score reports to the students, an error in the allocation of scores at Yamagata University was exposed by request from an applicant for scoring disclosure.

“The error was made known only after a student requested disclosure of the scores.”

“When I started the lawsuit, people kept asking me, “why do you want to know the score as you have already passed the exam?” But it became apparent that it is crucial to inform students of their test scores, regardless of whether or not they are accepted by a university, to deliver entrance examinations accurately and fairly. I was happy to find that what I felt when I was a university student was right.”

Why do we need to make our voices heard

More than twenty years have passed since then. Nowadays, we live in the era of the information society, and the issues surrounding public institutions and personal information have become even more sensitive.

“People’s attitude towards discussing key issues has changed across society. There is also a continuing diversification and multi-polarization of opinions. Present-day society is often strongly influenced by catchy, extreme opinions that appeal to people’s emotions. We must focus on encouraging open and fair discussion,” Miki says.

“We should openly share and discuss information issues so that more people can understand them. When it comes to information disclosure, we must not stop at criticizing the authorities for classifying certain information as non-public to make a real change. For public organizations, information disclosure offers the opportunity to show how they are doing their jobs properly.”

She also said that it is necessary to think about how to foster an open and transparent dialogue about information disclosure as a means of gaining the trust of the general public.

“It’s important that there are people who speak up against the status quo,” Miki says.

“If no one asks for an explanation, things will go on as before on the premise that such questions will never be asked. If no one speaks up, then nothing is going to change.”

“Some people are satisfied with how things are, or they are just not aware of problems until a crisis point. Those who are in need are usually hidden from public view. And the more vulnerable you are in society, the less likely you can have your voice heard. I believe that we can create a better system of safeguarding information by questioning whether certain information should be disclosed or not.”

Miki’s ongoing mission in the field of information disclosure and personal information protection is a form of democratic control of administrative organizations. Any actions by public bodies must be carefully monitored and kept under constant review. Her years of commitment to the cause of information privacy tells us that the right to know is one of our weapons to engage in this fight.

“The right to know is important,” says Miki. “But it’s not something that you can wait for someone else to protect or guarantee for you. It’s something that you, as an individual, have to fight to get.”

“One you have a system in place, it does not end there. It is not enough to have a system. Things won’t change unless you keep on excising your rights to make a better society. There is no use in being angry over unfair and unjust social mechanisms. It’s far more productive to get out there, use what you’ve got, and do what you can. We may or may not be able to change the existing system. For example, the dialogues between citizens and legislators about information privacy have led to the amendment to the Basic Resident Registration Act. This tells us that there always something we can do.”

Miki’s focus is firmly fixed on creating a better future beyond this litigation.

Interview and text by Yuko Haraguchi

Photography by Ooki Jingu