I am asking for help because it’s impossible for me to return to my home country. That’s the only thing that differentiates me from you as a human being.

2023.2.28

2023.2.28

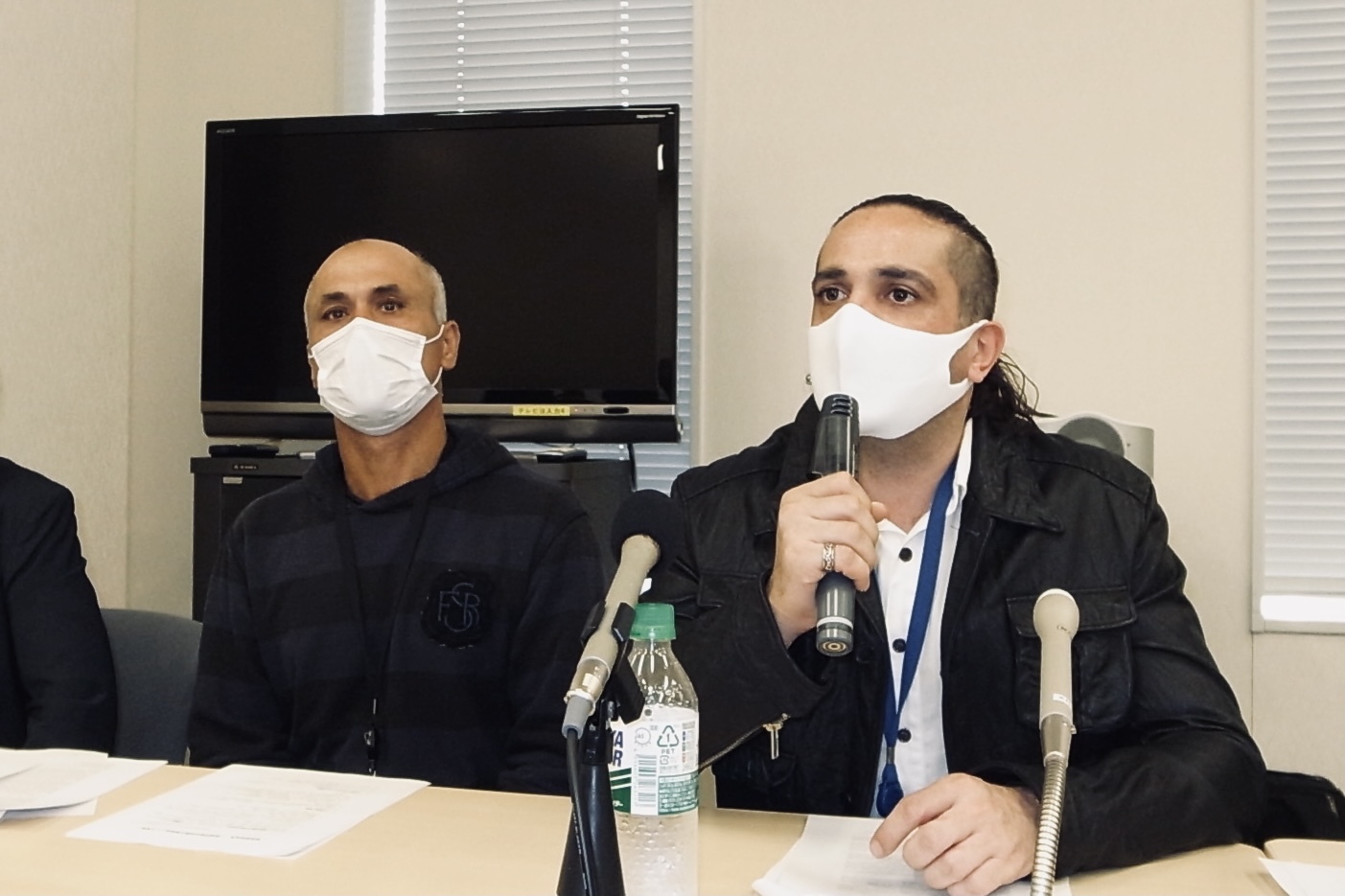

Story of a refugee from Iran, Safari, and his lawyer, Ms. Komai

In Japan, the acceptance rate of refugee applications is below 1%. When the application for recognition of refugee status is denied, the Immigration Bureau has the right to detain the applicants. However, many are placed on provisional release under certain conditions. As a result, those who were denied refugee status stay in Japan on provisional release, and they go to the Immigration Bureau for the extension of provisional release every time it expires.

Safari Diman Heydar from Iran has requested the extension every two months since he first applied for refugee status. One day, however, his request was suddenly denied. The Tokyo Immigration Bureau detained him on June 8th, 2016 without any explanation. The detention went on for 1,357 days.

Since the 1979 revolution, Iran has been under theocracy in which the clergy has absolute ruling power. Fleeing political persecution in his home country, Safari came to Japan in 1991. He has lived in Japan for 32 years, which is already much longer than the time he spent in his home country.

Handcuffed and roped despite not being criminals

The Immigration Bureau detains foreign nationals who have lost or do not have their status of residence for any reason, regardless of circumstances, and they will deport them to their home countries in principle.It means that even those who have fled persecution in their home countries and are seeking asylum as refugees or those who are living with their Japanese spouses or families can also be detained.

Since the pandemic in 2020, the number of detainees at the East Japan Immigration Center in Ushiku, Ibaraki Prefecture, has decreased to about 20 to 30. However, in 2016, there were approximately 250 detainees, and from 2017 to 2019, there were over 300 detainees, and the detention period was prolonged.

“There are single rooms, but usually, detainees are placed in small rooms with other three or four detainees and they are all from different countries and religions and speak different languages. The rooms are locked from the outside except during free time, and even when you are allowed to leave the room, all you can do is just to walk on a narrow corridor. Those who don’t speak Japanese have a harder time, and everyone is under a lot of stress, so they fight over every little things,” Sarafi explains.

“Detainees are allowed to exercise for 40 minutes per day in a facility gym. At first, many exercise for their health, but usually, they soon lose the motivation and stay in the room.

If you have a headache and want to see a doctor in the detention center, you first have to fill out an application form. It takes at least two weeks to see a doctor, three weeks on average, and until then you are given over-the-counter painkillers. You get sick in there, even if you don’t want to.”

Detainees are not criminals. Yet when they go to outside hospitals, the guards handcuff them and surround them from their left, right, and back. This controlling treatment deeply hurt the detainees.

“When I was allowed to go to the hospital, they handcuffed me and tied a rope around my waist like I was a dog. It was embarrassing and very uncomfortable to be seen by hospital staff and other patients. I was so uncomfortable that I wanted them to write on a piece of paper and put it on me to let them know that I was merely a refugee claimant.

Hunger strike, the only way left to protest against unreasonable treatments

One time, a few craftsmen came to repair the asphalt in the gym. One of them, an elderly man, said to the guard, “Everyone here is a criminal, aren’t they?”

Safari heard it and talked to him, “That is not true. We are not criminals.” He responded, “Then why are you here?”

Sarafi made a complaint to the guard for the first time. The guards and personnels at the Immigration Bureau would not give out the correct information, which results in detainees being regarded as criminals.

It was at that time that Safari, who had put up with a lot of unreasonable treatments in the three years since the beginning of his detention, decided to go on hunger strike.

“During my detention, I applied for provisional release about 10 times, but it was never accepted. I wanted to know why, so I also made a request for information disclosure. The 20-page documents I was given were almost all blacked out. Hunger strike was the only way left for me to protest.”

Detainees, even those who are coping well at first, gradually lose their physical and mental balance. Safari developed constant stomach ache, he had trouble sleeping at night, and he had to take more and more medications.

“After I started the hunger strike, I started having depressive symptoms and I was taking six tranquilizers and sleeping pills. One of the pills was very strong, and the doctor told me, ‘Mr. Safari, you shouldn’t take too many of these pills,’ even though he prescribed them himself.”

Safari began his hunger strike in June 2019 and he was finally granted provisional release in July. However, the provisional release turned out to be only for two weeks.

“There were other detainees who went on hunger strike and were granted provisional release. But I remember the guard telling me, ‘They will be detained again before you are granted provisional release.’ All they wanted was to stop us from going on hunger strike. That’s why they temporarily let us out.”

They needed to avoid detainees going on hunger strike because a Nigerian man who was also on hunger strike had recently died of starvation at the Omura Immigration Center in Nagasaki. His death shocked other detainees, but at the same time, it encouraged more detainees to go on hunger strike against the Immigration Bureau.

The moment when the last trust was shattered

“When I first heard that the provisional release was only for two weeks, I thought it was a threat from the Immigration Bureau,” recalls Ms. Komai. “They might not detain them again after the release and might extend the provisional release every two weeks. But even if they might not detain them again, that would be an incredible stress for those who are on provisional release. How could they even try to release and detain them on hunger strike… At that moment, I heard within me the sound of the last trust I had in the Immigration Bureau snapping. I had never thought that the Cat and Mouse Act the British authorities played with suffragettes would be replicated in 21st century Japan.”

Suffragettes are members who led the women’s suffrage movement in the UK in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. When they were jailed for protesting, the suffragettes resisted with a hunger strike. In response, the government force-fed them. In addition, the government passed a law to temporarily release those who had gotten sick by hunger strike and then reincarcerate them once they recovered in order to avoid responsibility for their possible deaths. This was the Cat and Mouse Act, which drew much criticism in British society at the time. The same evil law that was passed a century ago has now been in practice in Japan.

“Every detainee has been detained for years, and they are all desperate to get out. Even when you know that someone got detained again after being released for two weeks, you would still have a little bit of hope that maybe you will not be like them. But the Immigration Bureau issued two-week provisional releases three times. I brought a medical certificate that a psychiatric hospital issued for Safari, but the Bureau would not even look at it. They just wouldn’t, at all.”

If the hunger strike continues and another death by starvation occurs, the public will turn a harder eye on the Immigration Bureau. The reason behind issuing a two-week provisional release could be that they want to put detainees under incredible stress and almost expect them not to return to the Bureau after the two weeks, then they would have a valid reason to capture and detain them again.

“They have completely exceeded the bounds of what is permissible under the system,” Ms. Komai says, without hiding her indignation.

“It would make a whole difference if you knew in advance until when you would be detained. The mental stress of not knowing when you will be able to get out is extremely severe, and it brings to our mind the Nazi concentration camps depicted in “Night and Fog”. But Safari did not escape. How hard it must have been for someone like him to go back to the Bureau……”

When Ms. Komai looked over at him, Safari responded, saying “I knew I couldn’t betray the people who had believed in me and become my guarantor, and the people who had taken care of me. What the Bureau is doing is really terrible, but as a refugee, I am asking this country to help me, so I thought it would be wrong to run away.”

“But,” Safari continues, “You are detained for three years, you get a two-week provisional release, you know you will be detained again after, then you no longer care what happens to you. Obviously no one wants to go back there to be detained again. I can’t help but understand why some people run away.”

Japan’s Immigration Bureau violates international human rights law

The UN has an expert group, the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD), which investigates physical detentions suspected of being arbitrary in accordance with a United Nations Human Rights Council resolution.

A group of five lawyers including Ms. Komai, representing Safari as well as Denis, a Kurdish national who was also detained for a long period of time, reported to the WGAD in October 2019 that their detentions violate Article 9 of International Covenants on Human Rights. In response, the WGAD investigated and issued a recommendation to the Japanese government on September 28, 2020, stating that “the long-term detention of foreigners by the Immigration Bureau is a violation of international law.”

However, the government did not change its detention practices nor compensate Safari and Denis. Therefore, Safari and Dennis, along with their legal team, filed a lawsuit against the government, alleging that the detention was illegal and in violation of international law under the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act (the Immigration Law).

Although they had the backing of the United Nations, it must have taken a great deal of courage for Safari to become a plaintiff in a lawsuit against the government.

Safari says, “Even Japanese people would almost always lose a lawsuit against the government, so that’s definitely scary, and I am still afraid of the Immigration Bureau. After the hunger strike, we put our names and faces out in the open at a press conference. I was scared because few foreigners who had been detained in Japan would come out in public, but I was encouraged to do it because my lawyers are good people. I am not weak as a person, and I have nothing to be afraid of. But I just don’t know what will happen to me when I go to the Bureau. When you are detained, you don’t know when you can get out. That is the scariest part. When I go to the Bureau to apply for an extension of my provisional release, I always think that I might get detained again.”

The Immigration Bureau conducts examinations for provisional release, but there are no clear criteria for the decision. If you ask them for a reason for their decision, you will only get “We cannot answer about individual cases.” What is unacceptable in most other places is somehow being practiced as if it was normal at the Bureau.

In this country of democracy

In April 2016, an internal notice was issued within the Immigration Bureau stating that “it is an urgent task to significantly reduce the number of illegal residents and other foreigners who cause social unrest by the year of the Tokyo Olympics.”

Lawyers and supporters who work on Japan’s immigration issues all saw how the notice came into effect. After the notice was issued, provisional releases were no longer issued and detention became more prolonged.

However, the number of detainees decreased drastically after the pandemic began in 2020 and the Immigration Bureau changed its detention policy to actively issue provisional releases in order to prevent the spread of infection in the detention centers.

There is no data to support the Immigration Bureau’s claim that a large number of foreigners who are released from the detention centers cause major public safety issues. Safari and Ms. Komai both say, “Now that it’s clear that their claim is not true, they are trying to move from treating foreigners as criminals to now treating them as terrorists.”

A proposed amendment to the Immigration Law is to be reintroduced in the 2023 ordinary Diet session. It would allow for the repatriation of those who have applied for refugee recognition more than once under certain conditions in order to, in their words, “facilitate the repatriation of those who evade repatriation.” However, Japan’s refugee recognition rate in 2021 was less than 1%. Several human rights groups have expressed strong opposition to the proposal, stating that it will reduce the protection of refugees who should be protected and it will put their lives and human rights in danger.

“I have lived in Japan for 30 years and what bad things have I done? What public safety issues have I caused? If there is anything I did, I would like to know. I have made many friends since I came to Japan. You can live your life only once, so I want to enjoy my life as much as possible. I am talking to you all right now, but I don’t know what will happen when I leave this room. You never know when you will die. I want to live my life, making good memories. I am asking you for help because it’s impossible for me to return to my home country. That’s the only thing that differentiates me from you as a human being.” Safari turns his straight gaze toward us.

“Because I have seen with my own eyes that inside the detention center, the Immigration Bureau would really do whatever they want. In a way, they are like the government in my home country. Not in Iran or North Korea, but in this country of a democracy, foreigners are discriminated against. That is very unfortunate.”

Ms. Komai continues, “Even if you are poor, being in your own country, where you have family and friends, should be better than being in a detention center. But because there are reasons why he cannot return to his country, and because he is at risk of political persecution if he returns, Safari is applying for refugee status.”

At the 2022 FIFA World Cup, Iran’s national team, knowing the risk of being broadcast live to the world, expressed its anti-government intentions by not singing the national anthem in support of the domestic protests happening at the time. Late last year, a soccer player was sentenced to death for participating in women’s rights protests in Iran.

“Safari cries, saying ‘It hurts me that young people are dying in such a cruel way in Iran, and I can’t do anything to help.’ I want Safari to be recognized as a refugee as soon as possible.

United Nations Human Rights Committee raises concern on “Karihomensha” (those on provisional release)

“I’m sick and tired of not being able to work. After all, I loved working.”

When we asked him what his life is like now, Safari responded with a puzzled look on his face. His support group pays rent for him. He cuts back on food and manages to make ends meet.

Those on provisional release are not allowed to work, to sign up for national health insurance, and to travel beyond their home prefecture without a temporary travel permit. Their life is heavily constrained just like in the detention centers.

The United Nations Human Rights Committee issued a report in November 2022, and they used the term “Karihomensha” (those on provisional release) without translating it into English. The use of the term shows their concern.

Ms. Komai points out that the cruelty and abnormality of Japan’s provisional release system for foreigners have drawn international concern. She continues, “If I were put in the same situation that karihomensha are in, how would I live? To have a job and work is not only for earning money, feeling daily fulfillment, paying taxes and being a member of society. It is also a way to find meaning in life. Taking that away from people is by no means just too cruel.”

Safari says, “My supporters and friends are helping me because they have known me for a long time and they know what I am going through. But if the Bureau allows me to work, I will work, pay taxes, and spend money as a consumer just like anyone else.”

Safari’s words echo the sentiments of those on provisional release who are in the process of applying for refugee status.

“I want to live in Japan because it would be dangerous to go back to my own country. I had always worked before I was detained, and of course I would like to work if I could. I am comfortable with Japanese culture and customs, and I consider myself to have been raised in Japan. 20 years ago, I might have had the option of going to another country. But after living in Japan for 32 years, where would I go now? No matter how much I think about it, the only place I can be is in Japan. Even if the political situation in Iran changes and it would allow me to return, I will have to start from scratch. There is no foundation for me to live there. My foundation is only in Japan.”

To reform laws and systems to comply with international law

“It is very difficult to get an opinion from the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention. But the working group pointed out that what the Immigration Bureau does is wrong. If the Japanese government had reflected on this, we might not have had to start the lawsuit,” says Ms. Komai.

“But the government not only ignored the criticism, they showed no remorse or desire to comply with international law, as evidenced by the fact that they even protested to the UN. Safari and Dennis are the ones who filed the lawsuit, but they are not the only ones, and there are many other detainees who have been victims of arbitrary detention. We would like to reveal the truth and receive legal recognition from the court. We hope that this will lead to legal and institutional reform that complies with international law. With this in mind, we have started the lawsuit.”

Safari says, “If the system does not change, the same thing will continue to happen. Eighteen people have lost their lives in the detention centers since 2007, and some of them took their own lives. They were left to die because of the Immigration Bureau’s unfair practices. The problem with the Immigration Bureau is that their unfair practices are not known to the outside world. No personnel has ever been punished. If those at the top were held accountable and punished accordingly, the situation would not be this terrible.”

Detainees call the security officers who work in the detention centers “Mr./Ms. in Charge.” They wear name tags, but they do not have names on them; instead, they have a combination of letters and numbers.

Why don’t they put their names on their name tags? Every time we visit the detention centers, we cannot help but think that, if their names were known, they would restrain themselves from doing anything that might cause trouble. However, the Immigration Bureau is the opposite of publicness and openness. When we request disclosure of information to the Bureau, their documents that come out are almost always blacked out.

“Even a government like that…… No, I love my country, so I should not be saying it that way……. But even a government like that, Iran accepts much more refugees from Afghanistan and Syria than Japan does.”

Safari’s words never fade away.

Interview and text by Kyoto Tsukada

Photography by Yoko Akiyoshi

Edited by Orie Maruyama

Translated by Reiko Inoue and Tracey Cui