夫婦別姓も選べる社会へ!訴訟 Lawsuit for a Society Where Couples Can Take Separate Surnames!

現行法上、カップルが婚姻するには、一方が他方の名字に変更しなければなりません。実際は、結婚する女性の約95%が男性の名字に変更しており、名字の変更を望まない人は、アイデンティティの喪失など様々な不利益を被っています。結婚しようとすると、一方が名字を諦めるか、さもなければ結婚自体を諦めるかという過酷な二者択一を迫られるのです。私たちはこの現状に終止符を打ち、夫婦が別姓も選べる社会の実現を目指します。 Japanese laws require one of the partner to change their surname to the other partner upon marriage, predominantly ending up with women adopting men’s surname. This imposes disadvantages, such as identity loss, on those wishing to keep their surnames. Couples face a tough choice: either sacrifice the surname or forego the legal marriage. We strive to end this situation and advocate for a society where couples can take separate surnames.

はじめに

みなさんは、パートナーと結婚後の名字について話し合ったこと、自分が将来結婚するときに名字を変えるか相手に変えてもらうかの選択をしなければならないことを考えたことはありますか。

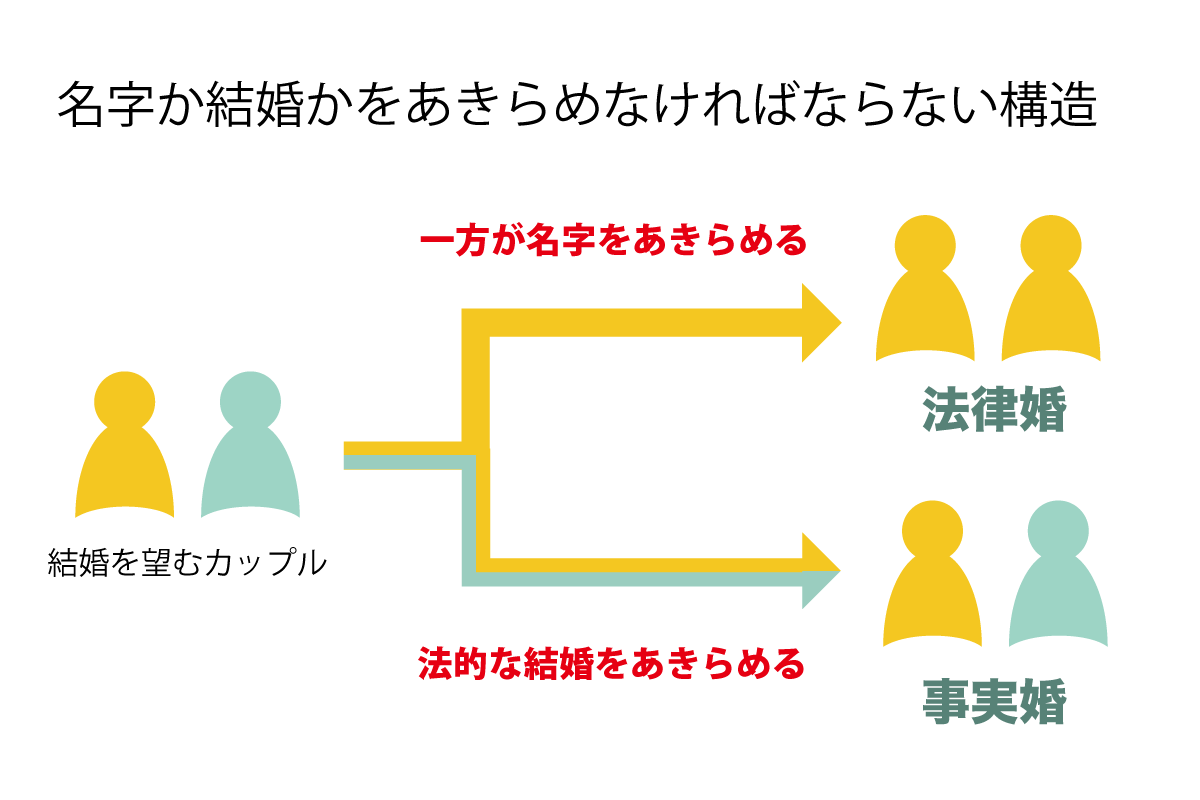

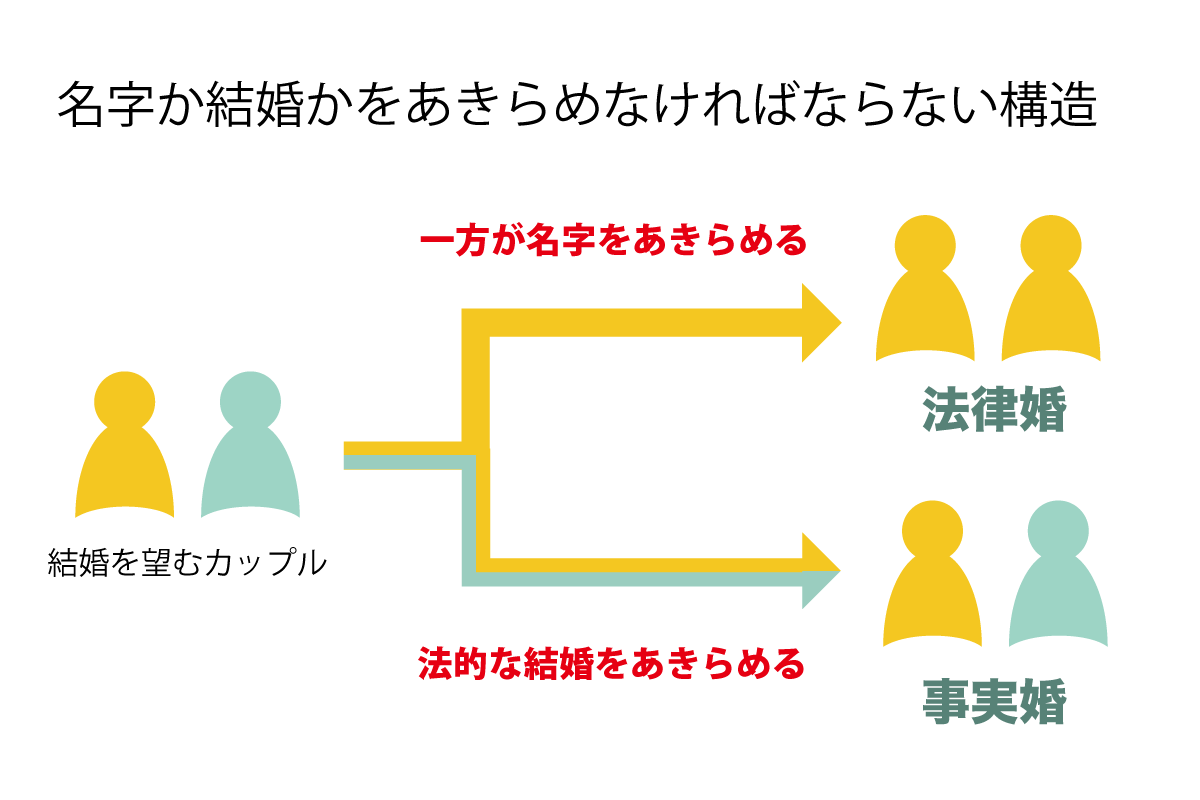

現在の法律は、結婚するカップルに対し、例外なく一方が他方の名字に変更するよう求め、夫婦が同じ名字を名乗ることを強制しています(夫婦同姓制度)。

夫婦同姓制度の下では、カップルの双方がそれまでの名字を維持したまま結婚することはできません。もし結婚を希望するのであれば一方が名字を変えるしかなく、そのままの名字を名乗ることを希望するのであれば法律婚そのものを諦めるしかない過酷な選択を迫られています。

しかし、名字を変えるとさまざまな不利益があります。

① アイデンティティの喪失

名前は、個人の人格と深く結びついていますが、結婚に伴って名前の一部である名字を変更することで以前の名前で呼ばれることが減り、これまでの自分がなくなっていくように感じる人もいます。

② キャリアの断絶

人は社会生活を送る中で、自分の名前に結びついて仕事上のキャリアや社会からの信頼や信用、人間関係を築いていきます。けれども、名字を変えることで、これまで築き上げてきたキャリアや信頼、人間関係が、結婚後の自分から切り離されてしまうこともあります。

③ 通称使用 / 併記の手続きの負担と公的効果の不十分さ

名字の変更に伴い、公的機関や金融機関で変更手続きを無数に強いられる負担もあります。その負担は法律で一律のものではなく、所属する機関によって違いがあります。

旧姓の通称使用や併記が認められても、不利益はなくなりません。

公的機関など戸籍上の名字の使用を求められるところも少なくなく、場面により結婚前と後の名字を使わなければならなくなります。

上記のような不利益が存在する中、現在結婚するカップルの約95%は、夫の名字を選択しています。

カップル双方が名前を変えることを望まない場合、話し合いは極めて困難であり、また、「妻は夫の家に入る」という考えが未だ根強い中、特に女性が話し合いの中で感じるプレッシャーは甚大です。

このような不利益が圧倒的に女性に偏っている現状は、女性の活躍が社会でますます進んでいる中で女性にとっての重い足枷となっており、経団連からも女性活躍を推進するための最優先課題として選択的夫婦別姓の導入の検討が要望されています。

結婚後も双方が結婚前の名字を名乗り続けられる選択肢(選択的夫婦別姓)があれば、カップルが結婚後の名前をめぐって葛藤する必要はなくなります。

最高裁大法廷はこれまでに2回、国会で決めるべきことであるなどとして夫婦同姓制度は合憲だと判断していますが、今度こそ選択的夫婦別姓を実現するべく、12名が原告として立ち上がり第3次訴訟を提起することにしました。

▲第3次訴訟、原告と弁護団が東京地裁に入廷する様子

原告が立ち上がった経緯

原告 内山由香里さん

法律婚により25年ほど通称使用を続けてきました。望まない改姓により、自分の存在を公的に証明する運転免許証、健康保険証、パスポート等の姓を変更せざるを得なくなり、さらには銀行口座や保険などまで芋づる式に戸籍姓になっていきました。結局、通称は肝心なところで使えず、むしろ自分が使いたい生来の名前が本当の名前ではないことを日常的に痛感させられ、不快感や喪失感を突き付けられてきました。

私は便宜上、同じ相手との結婚と離婚を3回経験し3回とも改姓していますが、改姓しない側は日常も周りとの関係も1ミリも変わらないので、改姓した側の不利益が想像できない。これが不均衡でなくて何なのでしょうか。

何も変わらないまま30年以上が過ぎてしまいました。子どもたちの世代が同じ理不尽に直面することに我慢ができなくて、勇気を出して声を上げることにしました。

原告 黒川とう子さん・根津充さん

現在の夫と出会い、パートナーとして一緒に暮らしていきたいものの、長年共に生きてきた名前を失いたくなく、またそのような思いを相手にもさせたくなく、事実婚の選択を提案しました。夫は私の考えを聞くうち、仮に男性側が姓を変えることを事実上強制されるような社会であったならと想像し、同氏制に疑問を持つようになりました。夫は姓が同じであることと家族の一体感や仲の良さとは全く関係がないことを実感もしており、ふたりで事実婚を選択しました。

17年近く事実婚を続け、子供も育ててきましたが、共同で住宅ローンを組める金融機関がほとんどない、父親に子供の親権が当然にない、何かあった時に互いが互いの法定相続人になれない、医療機関で手術等の同意ができるかどうかわからないなど、正式な夫婦と認められないことでいざという時にどうなるか分からない不安を常に感じています。

原告 上田めぐみさん

選択的夫婦別姓が話題になり、法改正の機運が高まった1990年代前半、私は中学生でした。「どうして結婚すると女性ばかり姓を変えるのだろう」と共感し、「私も変えたくない」と思い始めました。自分が大人になる頃には法律は変わっているだろう、と信じていたのにもう30年以上が経過。2013年に結婚式を挙げた私も当事者になりました。

2015年、第1次訴訟の最高裁判決の日は、出張先のアフリカで合憲判決のニュースをネットで知り、あまりのショックに半年ほど耳鳴りと目まいが止まりませんでした。

「もう待っていられない、自分が動かなければ」と思い、第2次訴訟では、別姓訴訟を支える会事務局を担当しました。しかし、第2次訴訟でも違憲判断は得られず「今度こそ歴史を変えたい」という思いで立ち上がりました。国内外で自分の姓を選べず困っている、多くの人たちの想いを背負って闘います。

▲(左から)原告の根津充さん、黒川とう子さん、小池幸夫さん、上田めぐみさん、新田久美さん

▲原告の佐藤万奈さん、西 清孝さん

裁判の争点

原告らが求めるもの

⑴ 地位確認:夫婦双方の結婚前の名字を維持したまま結婚し得る地位にあることの確認

⑵ 違法確認:(⑴が認められない場合の予備的請求)国が、法律を改正しないことにより、原告らが夫婦双方の婚姻前の氏を維持したまま婚姻することを認めないことは違法であることの確認

⑶ 国家賠償請求:国が、法律を改正しないことによって、原告らが夫婦双方の結婚前の名字を維持したまま結婚することを認められなかったことにより、原告らに生じた損害の賠償

法的な根拠

1. 憲法違反

別姓という例外を許さない夫婦同姓制度は、憲法13条・憲法24条1項に違反すると同時に、個人の尊厳と両性の本質的平等に立脚した立法を求める憲法24条2項にも違反しています。

名前と結びついている個人のアイデンティティや社会的な認識という利益は、個人の尊厳の基盤を成すものであり、人格的生存に不可欠な利益を保障する憲法13条で保障されています。

また、憲法24条1項は、結婚をすることについての自由かつ平等な意思決定を保障しているといえます。

第24条1項 婚姻は、両性の合意のみに基いて成立し、夫婦が同等の権利を有することを基本として、相互の協力により、維持されなければならない。

しかし、夫婦同氏制度は、結婚前の名字を名乗り続けることを希望する者に対し、名字を諦めて結婚するか、結婚を諦めて名字を維持するかの二者択一を迫り、憲法で保障される権利を制約しています。

このような権利を制約するためには、結婚に夫婦が別々の名字を名乗るという例外を許さないことに必要性と合理性がなくてはいけませんが、それらも以下のように認められません。

⑴ 結婚の本質との無関係さ

結婚の本質は「両性が永続的な精神的及び肉体的結合を目的として真摯な意思をもつて共同生活を営むこと」にありますが、名字が一緒であってもなくてもこの意思には関係がなく、合理性がありません。

⑵ 旧姓 / 通称使用の不十分さ

近時、改姓の不利益を緩和するために、旧姓を通称として使用できる場面が広がってきています。例えば、2019年11月には住民票・マイナンバーカードの旧姓併記が可能になり、2021年4月には旅券の旧姓併記の要件が緩和されました。

しかし、公的証明書の記載事項について、戸籍上の姓と通称に違いがあるために手続きが煩雑になったり、旧姓併記ができたとしても海外で認められなかったりする場合があります。混乱が生じる度に、結婚に伴って改姓したというプライバシーを開示して説明しなければいけません。

このように、通称使用には様々な限界と弊害があります。通称使用によって改姓の不利益が解消されることはありません。

(3) 社会的状況や意識の変化

男女ともに晩婚化が進み、また女性の社会進出が進む中で、結婚前の名前で築いた実績や信用は大きくなり、名前を維持する必要性が高くなっています。

また、選択的夫婦別姓に対する調査では、若年層の87%が賛成。中でも女性若年層の賛成は91%という結果が出ています。2024年1月には、経団連が選択的夫婦別姓制度の導入を政府に求めるに至っています。

このほかに、最高裁は夫婦同姓制度を合憲とする理由として、家族の呼称を一つに定めることに一定の意義があること、夫婦別姓の場合には子の名字の定めや戸籍の記載方法などについて議論の余地があることなどを挙げていますが、それは夫婦別姓という選択肢を一切認めないことの理由にはなりません。

2. 国際条約違反

⑴女性差別撤廃条約違反

女性差別撤廃委員会は、1994年に一般勧告21を採択し、婚姻前の名字を変更するよう強制することは、女性の「自己の姓を選択する権利」の否定であると明言しています。

⑵自由権規約違反

自由権規約委員会は、1990年に一般的意見19を採択し、「自己の婚姻前の姓の使用を保持する権利又は平等の基礎において新しい姓の選択に参加する権利」の保障を掲げています。

また、2000年には一般的意見28を採択し、これらの権利に関して性別の違いに基づく差別が起きないことを確実にしなければならないとしました。

さらに、女性差別撤廃委員会は2003年と2009年と2016年の3度にわたって、また、自由権規約委員会は2022年に、日本政府に対し、夫婦同姓制度が差別的であるとして是正を求める勧告を行っています。

これまでの経緯

1991年の法制審議会において、夫婦同姓制を含む婚姻制度等の見直し審議が行われ、1996年には「夫婦は、婚姻の際に定めるところに従い、夫若しくは妻の氏を称し、又は各自の婚姻前の氏を称するものとする。」との規定を含む民法改正の要綱案が答申されました。

しかし、要綱案は与党の法務部会の了承を得られず、国会提出に至らなかった過去があります。

これまでも最高裁は2度大法廷を開いて審理しましたが、立法府の判断に委ねるとの判断がなされ、要綱案答申から約30年が経過した現在に至ってもなお、選択的夫婦別姓制度の導入はなされていません。

第1次選択的夫婦別姓訴訟

2011年、選択的夫婦別姓の実現を目指して、最初の訴訟を提起しました。

第1次訴訟では、事実婚カップルや法律婚で改姓した女性が原告となり、国家賠償請求訴訟では、民法750条の憲法13条違反、憲法14条1項違反、憲法24条違反、女性差別撤廃条約違反を主張しました。

2015年の最高裁大法廷判決では合憲とされましたが、15名中5名の裁判官(うち3名が女性)が、夫婦同姓の強制は違憲であるとの意見を述べました。

▲最高裁大法廷判決の報告会で

第2次選択的夫婦別姓訴訟

第2次訴訟では、複数の事実婚カップルやニューヨーク州で別姓のまま婚姻した日本人同士のカップルが原告となり、①別姓婚姻届の受理を求める家事審判、②立法不作為に基づく国家賠償請求訴訟、③海外での別姓婚の婚姻関係の公証を受けうる地位の確認請求訴訟を提起しました。

①について、2021年に最高裁によって再び大法廷で審理が行われ、合憲判断がなされたものの、15名中4名の裁判官(うち1名が女性)が違憲意見を述べました。

▲第2次訴訟・広島地裁での弁論期日に

担当弁護士のメッセージ

第1次・第2次訴訟では残念ながら合憲判断となりましたが、合計10名もの最高裁判事が夫婦同姓制度は違憲であると述べ、学界でも違憲との見解が多数説となるなど、得たものも多くありました。

法制度はすべての人が幸せになるために存在するもので、憲法は人権を侵害するような法制度を許容してはいません。

これを最後の訴訟とすべく全力で臨みますので、ご支援の程どうぞ宜しくお願い致します。

弁護団長 寺原真希子

弁護団の紹介

寺原 真希子(弁護士法人東京表参道法律会計事務所)

三浦 徹也 (あさひ法律事務所)

野口 敏彦 (弁護士法人龍馬 あおやま事務所)

井桁 大介 (宮村・井桁法律事務所)

大谷 秀美 (広尾パーク法律事務所)

折井 純 (美竹やさか法律事務所)

亀石 倫子 (法律事務所エクラうめだ)

川尻 恵理子(ハロー法律事務所)

川見 未華 (樫の木総合法律事務所)

橘高 真佐美(大谷&パートナーズ法律事務所)

木村 いずみ(北新居・青木法律事務所)

榊原 富士子(千川通り法律事務所)

塩生 朋子 (四谷共同法律事務所)

芹澤 眞澄 (新宿西口法律事務所)

竹下 博將 (弁護士法人つくし)

棚橋 桂介 (弁護士法人フロンティア法律事務所)

谷口 太規 (弁護士法人東京パブリック法律事務所)

寺林 智栄 (NTS総合弁護士法人 札幌事務所)

早坂 由起子(千川通り法律事務所)

久道 瑛未 (早稲田リーガルコモンズ法律事務所)

渕上 陽子 (美竹やさか法律事務所)

松田 亘平 (美竹やさか法律事務所)

溝田 紘子 (東京弁護士会所属)

山崎 新 (アイリス法律事務所)

山田 暁子 (みなみ大通法律事務所)

※弁護団員の自己紹介は、別姓訴訟を支える会のホームページをご覧ください。

https://bessei.net/lawyers/

資金の使途

訴訟費用:印紙代・コピー代などの実費費用

学者に依頼する意見書費用:憲法学者や民法学者、行政法学者等の専門家に意見書を執筆していただくことを予定しています

リサーチ費用:選択的夫婦別姓に関する世論調査や氏に関する海外法制の調査など、多数の文献の取寄せや翻訳作業などを伴うリサーチの実施を予定しています

弁護団、原告などの交通費:係属裁判所の遠方に住む原告や弁護団員が出頭する際の交通費や、専門家の方などに裁判所にお越しいただく際の交通費を寄付金から支出する予定です

イベント開催・広報費用:この裁判に関するイベントや広報費用にも寄付金を用いたいと考えています

弁護士費用等:上記各費用を支出後、もし残高がありましたら、弁護団員の着手金、成功報酬、出張日当、別姓訴訟を支える会のみなさんの人件費等に活用したいと考えています

おわりに

選択的夫婦別姓は、これまで述べてきたように、カップルが同一の名字を名乗る選択肢の他に、カップル双方が結婚前の名字を名乗り続けるという選択肢を設ける、というものです。

同一の名字を名乗りたいカップルは、選択的夫婦別姓の下においても、従前どおり同じ名字とすることができます。

選択的夫婦別姓は、結婚前の名前を名乗り続けたいカップルの希望を実現する一方で、社会に大きな不利益を生じさせません。選択的夫婦別姓が実現すれば、社会全体の幸福が増進するといえるでしょう。

最高裁大法廷は、2015年と2021年の2度にわたって、夫婦同姓を強制する制度は合憲であると判断しました。合憲判断を覆すには高いハードルがありますが、憲法学説の変化や社会の意識の変化などを具体的に立証していけば、必ず違憲判断を獲得できると考えています。

そのためにはみなさまの力強い応援が必要です。

寄付や期日の傍聴、SNSでの拡散など、一人一人のアクションが大きな力になります。

選択的夫婦別姓の実現に向けて尽力してまいりますので、ご支援のほどよろしくお願いいたします。

▲第3次訴訟、東京地裁での提訴後に撮影したもの

Introduction

Have you ever imagined a situation like this: you and your partner are talking about your surnames upon marriage, but either you or your partner have to change the surname.

The current law in Japan requires a husband and wife to have the same surname upon marriage, meaning that one partner has to ask the other to change the surname (same surname system).

As such, couples in Japan cannot retain their own surnames upon marriage. When they wish to get married, they face the harsh choice between having one of the party change the surname, or giving up the legal marriage while maintaining their own surname.

Moreover, surname change begets all kinds of harm.

① Identity loss

A person’s name is deeply related to personal identity. By changing part of the name upon marriage, the old name will be used less often, and one can feel that they lose the selfhood that has been built up so far.

② Career/social relation disruption

In everyday life and during work, individuals use their names to accumulate their social trust and confidence from others, and cultivate social relations. If they change their names, the social relations and trusts could be disrupted.

③ Burden and insufficiency of using usual names and co-listed names

Changing one’s name also comes with the burden of having to go through countless change procedures at public and financial institutions. These procedures are not uniformly stipulated by the law, and can vary depending on the institutions. Even with the use of an old surname as a common name or co-listed name, this hurdle cannot be prevented. As it is quite common for a person to be asked to use the name on the family registry in administrative procedures, one can sometimes find oneself in a position where they need to use both surnames before and after marriage.

Along with such harms, about 95% of married couples choose the husband's last name.

If the couples do not want to change their names, it is very hard to have a conversation over this, and as the idea that “the wife should join the husband's household'' still persists, women are usually under great pressure when discussing this issue.

Such harms are overwhelmingly imposed on women and become a heavy shackle for women to take more active roles in society. In this regard, the Japan Federation of Economic Organizations (Keidanren) recommended surnames for married couples to be considered as a top priority issue.

If couples have the option to continue to use their original family name (selective separate surnames system for married couples), couples will no longer have to face these impediments.

The Grand Bench of the Japanese Supreme Court decided twice that the current same surname system for couples is constitutional, referring that it is a matter to be decided by the Congress. But the 12 plaintiffs have not yet given up and filed the third lawsuit in order to make the selective separate surname system for married couples a reality.

▲Entering the Tokyo District Court for the third lawsuit.

Stories of the plaintiffs

Plaintiff Yukari Uchiyama

I have continued to use my usual name for about 25 years after the legal marriage. Regardless of the unwanted name change, I am forced to change the name on my driver's license, health insurance card, passport, and even the names for bank accounts, insurance to my name as inscribed on the family registry. In the end, I was not able to use my usual name in any important situations. I suffer from the feeling that my name given at birth, which I want to use, is not my real name anymore, and I have a deep sense of discomfort and loss.

I have been married and divorced three times to the same person and changed my name all three times. The one who does not change their name does not change their daily life or their relationships with those around them at all due to the surname. So they cannot even imagine what disadvantages to the person who changed their name are like. How unfair is it?

I have been living with this unchanged situation for more than 30 years. However, I do not want the future generations to have to bear the same unfairness, so I chose to stand up for this lawsuit.

Plaintiffs Touko Kurokawa and Mitsuru Nezu

I met my current husband and wanted to live together as partners. However, I did not want to lose the name I had for many years, nor did I want to make the other partner think that they have to do the same, so I proposed a common-law marriage. As my husband listened to me, and started to imagine a society where men were effectively forced to change their surnames, he began to question the surname system. Having the same last name had nothing to do with family unity or happiness, so we decided to have a common-law marriage.

We have been in a common-law marriage for nearly 17 years and have raised children, but there are almost no financial institutions that allow us to jointly take out a mortgage, the father of course does not have custody of the child, we are not each other's legal heirs, and we cannot even sign on the operation consent form for each other at hospitals. We always feel insecure because we don't know what will happen if something happens and we are not recognized as a married couple.

Plaintiff Megumi Ueda

I was a junior high school student in the early 1990s, when the option of separate surnames for married couples became a hot topic and there was a growing momentum for legal reform. I had the same question, “Why do so many women change their surnames when they get married?'' and began to think, “I don't want to change my name.'' I believed that the law would have changed by the time I became an adult, but nothing changed after more than 30 years. Getting married in 2013 makes me a directly related party to this issue. In 2015, on the day of the Supreme Court's decision in the first lawsuit, I learned about the constitutionality ruling online while on a business trip to Africa, and was so shocked that ringing in my ears and dizziness tormented me for about six months. I thought, “I can't wait any longer, I have to take action,'' so in the second lawsuit, I took charge of the secretariat of the organization that supported the lawsuit. However, even in the second lawsuit, the ruling was not found to be unconstitutional. I think that “this time, I want to change history,” and I decided to stand up. I will fight for the wishes of many people in Japan and abroad who are unable to decide their own surnames.

▲(From the left)Plainiff Mitsuru Nezu, Touko Kurokawa, Sachio Koike, Megumi Ueda and Kumi Nitta.

▲Plaintiff Mana Sato and Kiyotaka Nishi.

Points in Dispute

Plaintiffs' Claims:

(1) Status confirmation that both spouses can marry while retaining their original surnames.

(2)Confirmation of illegality (subsidiary request in case (1) is not admitted) of the State's failure to amend the law to allow each spouse to marry while maintaining their respective original surnames.

(3) State compensation: as the state fails to amend the law, the state shall compensate the plaintiffs for damages caused by the failure of recognizing the marriage of two individuals who keep their original surnames.

Legal Argument

1. Constitutional violation

This same surname system which does not allow separate surnames of spouses violates Article 13, and Article 24 (1), as well as Article 24(2) of the Japanese Constitution, which requires legislation to be enacted from the standpoint of individual dignity and the essential equality of the sexes.

Names are inextricably connected to one's sense of self and identity, which constitute the foundation of individual dignity. As such, it falls under the umbrella of Article 13 of the Constitution, which protects rights and personal interests that are indispensable to personal existence.

Moreover, Article 24(1) ought to be interpreted as guaranteeing free and equal decision-making in marriage.

Article 24(1) Marriage shall be based only on the mutual consent of both sexes and it shall be maintained through mutual cooperation with the equal rights of husband and wife as a basis.

However, the current same surname system forces those who wish to retain their names before marriage to decide between either getting married by giving up their own names or giving up the legal marriage to keep their names. As such, it infringes on constitutionally-protected rights.

In order to justify such a constraint on rights, the prohibition on married couples to use separate surnames without exceptions must satisfy the necessity and rationality test. However, as shown below, it does not fulfill these criteria.

(1) Irrelevance to the nature of marriage

According to the Supreme Court, the nature of marriage lies in “two sexes sincerely engaging in cultivating a shared life with the purpose of enduring a durable emotional and physical union.” Having the same surname is irrelevant in this regard and therefore lacks rationality.

⑵ The use of original family name as a usual name is insufficient

In order to mitigate the disadvantages caused by change of surname, there is an increasing use of the original family name as the usual name. For example, from November 2019, it is possible to record both names on the residence certificate and my number card, and from April 2021, the rules for passports have given greater leeway.

However, the administrative procedure for many official documents is complicated when a person uses both registered and usual names, and even if both names are recorded, sometimes the maiden name is not recognized overseas.

Moreover, everytime a problem occurs, one has to expose private details about their marriage to explain the situation.

As a result, the use of usual names is greatly restrained and cannot eliminate all the disadvantages that come with having to change one’s name.

(3) Societal beliefs and change in awareness

As both men and women are getting married later in life, and more women are entering the workforce, the achievements and credibility one builds under their original surnames increase, and hence, there is a growing need to keep using original surnames.

Additionally, according to a survey regarding the selective separate surname system for married couples, 87% of young people were in favor of choosing separate surnames, out of which 91% were women. In January 2024, the Japan Business Federation (Keidanren) requested the government to introduce the selective separate surnames system for married couples.

In its prior judgment, the Supreme Court has cited certain reasons to justify the constitutionality of the same surname system such as the significance of using a single name for family unity, and the potential for debate over issues like children's surname and the method of registering in the family registry in cases of separate surnames. However, these reasons do not justify the complete denial of the option for separate surnames.

2. Violation of International Treaties

(1) Violation of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women

The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women has stated, in its General Recommendation No. 21 (1994), that when by law or custom a woman is obliged to change her name on marriage, she is denied the right to choose her name.

(2) Violation of the Covenant on on Civil and Political Rights

The Human Rights Committee adopted General Comment 19 in 1990, guaranteeing the “right of each spouse to retain the use of his or her original family name or to participate on an equal basis in the choice of a new family name.'' Further, in 2000, it adopted General Comment 28, which stated that it must ensure there is no gender discrimination with respect to these rights.

Furthermore, the Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination recommended the Japanese Government to rectify the same surname system for married couples in 2003, 2009 and 2016, as it deemed it discriminatory. The Human Rights Committee also cautioned the Japanese government in 2022 that the same surname system for married couples is discriminatory. To date, the Japanese Government has not complied.

Summary of Prior Lawsuits

In 1991, the Legislative Council deliberated on a review of the marriage system, including the same surname system for married couples, and in 1996, it submitted a draft proposition for revising the Civil Code. The draft stated as follows: “A married couple shall, at the time of their marriage, take the surname of the husband or wife, or their respective original surnames, as determined at the time of their marriage.” Yet, the draft was not approved by the ruling party's Legal Affairs Subcommittee and was not submitted to the Diet.

In the two previous lawsuits, the Court decided to leave the issue to the discretion of legislators. However, as of now, 30 years after the proposed outline was submitted, the selective married couple surname system has yet to be introduced.

First lawsuit

A first lawsuit was filed in 2011 to seek the right of couples to take separate surnames upon marriage. The plaintiffs were common-law couples and women who had changed their surnames due to legal marriage. They claimed state compensation and argued that there was a violation of Article 750 of the Civil Code, Articles 13, 14(1) and 24 of the Constitution, as well as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women.

Although the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court ruled in 2015 that this system was constitutional, 5 out of 15 judges (3 of them women) expressed that forcing married couples to have the same surname is unconstitutional.

▲Briefing session after the decision of the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court

Second lawsuit

In a second lawsuit, the plaintiffs consisted of multiple common-law couples and Japanese couples who got married in New York state with separate surnames. The plaintiffs requested that ① domestic relations cases for adjudication accept the registration of marriages with separate surnames; ② state compensation based on legislative inaction; and ③ status confirmation that marriages overseas with separate surnames shall be notarized.

Regarding ①, the Supreme Court again held in a Grand Bench judgment in 2021 that it was constitutional, but 4 out of 15 judges (one of whom was a woman) expressed the opinion that it was unconstitutional.

▲Entering the district court of Hiroshima for the second lawsuit.

Message from the Lead Counsel

Although in the first and second lawsuits courts regrettably found the system to be constitutional, a total of 10 Supreme Court justices have stated that the same surname system for married couples is unconstitutional, and the majority in the academia stand for unconstitutionality. It can be said that we accomplished a lot.

The purpose of laws is to contribute to people's happiness, and besides, the Constitution does not tolerate laws that infringe on human rights.

We will put forth our utmost effort to ensure this lawsuit is the final one. We greatly appreciate your continued support.

Lead Counsel, Makiko Terahara

Legal Counsel Team

Makiko Terahara (Tokyo Omotesando Law and Accounting Office)

Tetsuya Miura (Asahi Law Office)

Toshihiko Noguchi (Ryoma Aoyama Lawyer Corporation)

Daisuke Igeta (Miyamura & Igeta Law Office)

Hidemi Otani (Hiroo Park Law Office)

Jun Orii (Yasaka Yoshitake Law Office)

Michiko Kameishi (Law Office Eclat Umeda)

Eriko Kawajiri (Hello Law Office)

Miharu Kawami (Kashinoki Sogo Law Office)

Masami Kikkata (Otani & Partners Law Office)

Izumi Kimura (Kitaarai/Aoki Law Office)

Fujiko Sakakibara (Senkawadori Law Office)

Tomoko Shioike (Yotsuya Kyodo Law Office)

Masumi Serizawa (Shinjuku Nishiguchi Law Office)

Hiroyuki Takeshita (Tsukushi Lawyer Corporation)

Keisuke Tanahashi (Frontier Law Office)

Motoki Taniguchi (Tokyo Public Law Office)

Tomoe Terabayashi (NTS General Lawyers Corporation Sapporo Office)

Yukiko Hayasaka (Senkawadori Law Office)

Emi Hisamichi (Waseda Legal Commons Law Office)

Yoko Fuchigami (Yasaka Mitake Law Office)

Kohei Matsuda (Yasaka Mitake Law Office)

Hiroko Mizota (Tokyo Bar Association)

Arata Yamazaki (Iris Law Office)

Akiko Yamada (Minami Odori Law Office)

*For self-introductions of the attorneys, please see the website for the organization supporting this lawsuit.

https://bessei.net/lawyers/

Use of Donations

Litigation expenses: Actual costs such as stamp fees and copying fees

Expert opinions by scholars: We plan to have experts such as constitutional scholars, civil law scholars, and administrative law scholars write the opinion.

Research expenses: We plan to carry out research that will involve ordering and translating a large number of documents, such as a public opinion survey regarding selective separate surnames of married couples and a survey of overseas legal systems regarding surnames.

Transportation expenses for lawyers, plaintiffs, etc.: We plan to use donations to cover transportation expenses for plaintiffs and defense team members who live far away from the court, as well as transportation expenses for experts and others to come to the court.

Event organization and public relations costs: We would like to use donations for events and public relations related to this trial.

- Attorney's fees: After paying the above expenses, if there is any remaining amount, we would like to use it for the initial fee of the legal counsel's team, success fee, daily travel allowance, and personnel expenses of the organization supporting the lawsuit.

Conclusion

A selective separate surnames system for married couples would allow couples to choose the same surname or to continue using their respective original surnames. This would allow people who want to keep their original surname to do so, without producing a negative impact on society. Besides, we believe that the realization of the selective separate surnames system will increase the overall wellbeing of society.

Both in 2015 and 2021, the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court has ruled that the system that forces married couples to have the same surname is constitutional. Although there are significant hurdles to overturn these judgments, we believe that if we are able to concretely substantiate changes in constitutional law theory and public awareness, we will certainly obtain a judgment of unconstitutionality.

We need your support to realize this goal.

The actions of each and every person, no matter the form it takes (donations, attending court hearings, sharing content on social media), wield considerable power.

We will put forth our best efforts to make the selective separate surnames system a reality.

▲Taken after the third lawsuit was filed in the Tokyo District Court.

選択的夫婦別姓の実現を目指して、2011年(1次)と2018年(2次)に裁判を提起してきました。夫婦同姓を強制する制度は違憲であるとの判断を今度こそ勝ち取るべく、弁護団一丸となって尽力します。

<連絡先>

〒100-8385

東京都千代田区丸の内2-1-1丸の内マイプラザ13階

あさひ法律事務所

弁護士 三浦 徹也(弁護団事務局長)

電話:03-5219-0002 FAX:03-5219-2221

Legal Counsel Team of the Third Lawsuit for a Selective Separate Surnames System for Married Couples

We filed lawsuits in 2011 and 2018 for the purpose of achieving a system where married couples have the option of taking separate surnames in Japan. We believe a law that requires couples to take the same surname upon marriage should be ruled unconstitutional, and we will do our utmost to win the lawsuit.

<Contact information>

〒100-8385

Asahi Law Office

Tokyo, Chiyoda City, Marunouchi, 2 Chome−1−1

Marunouchi Mai Plaza, 13F

Attorney-at-Law Tetsuya Miura (Executive Secretary of the Legal Counsel Team)

Phone: 03-5219-0002

Fax: 03-5219-2221

関連コラム

-

2024. 3. 8

あなたにおすすめのケース Recommended case for you

- 外国にルーツを持つ人々 Immigrants/Refugees/Foreign residents in Japan

- ジェンダー・セクシュアリティ Gender/Sexuality

- 医療・福祉・障がい Healthcare/Welfare/Disability

- 働き方 Labor Rights

- 刑事司法 Criminal Justice

- 公正な手続 Procedural Justice

- 情報公開 Information Disclosure

- 政治参加・表現の自由 Democracy/Freedom of Expression

- 環境・災害 Environment/Natural Disasters

- 沖縄 Okinawa

- 個人情報・プライバシー Personal information/Privacy

- アーカイブ Archive

- 全てのケース ALL